The Australian Government is now in caretaker period. During this time, updates on this website will be published in accordance with the Guidance on Caretaker Conventions, until after the election.

This section guides you through the actions you can take for yourself or in interactions with other people to prevent infections spreading. Good personal habits are key to reducing the spread of infection.

2.1 Immunisation

Immunisation is an effective way to prevent some infections. Immunisation uses a vaccine – often a dead or modified version of the germ – to trigger an immune response against a specific disease.1 This means the person’s immune system responds in a similar way to how it would if they had the disease, but with less-severe symptoms. If the person comes in contact with that germ in the future, their immune system can respond quickly to prevent the person becoming sick.

Immunisation can also protect people who are not immunised, such as children who are too young to be immunised, or people whose immune systems did not respond to the vaccine. This is because the more people who are immunised against a disease, the lower the chance that a person will ever meet someone who has the disease. The chance of an infection spreading in a community decreases as more people are immunised. Immune people are less likely to become infected, and this protects vulnerable people – this is known as ‘herd immunity’.

In certain situations, including outbreaks of some diseases in education and care centres, a vaccine can be offered to people after they have been exposed to the disease to reduce the risk of them getting the disease. Your local public health unit can offer specific advice if this happens. However, this is only used in special circumstances – immunising people before they come into contact with a disease is far more effective.

A note about the terms:

Both ‘immunisation’ and ‘vaccination’ are often used to mean the process of receiving a vaccine to create immunity.

The 2 terms have slightly different meanings:

- Immunisation is the process of inducing immunity to a specific germ by giving a vaccine or antiserum, or gaining antibodies by having the disease.

- Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine. If vaccination is successful, it results in immunity. In this guide, we have used ‘immunisation’ to talk about the general process, and ‘vaccination’ to talk about specific vaccines and receiving a vaccine.

Immunisation for children

The National Immunisation Program Schedule provides a list of the vaccines currently recommended for all children. Additional vaccines are recommended for Indigenous children in specific jurisdictions and for children with specific medical conditions.

The Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) recommends annual immunisation against influenza for all people aged over 6 months to prevent influenza infection and complications associated with influenza infection.2 Immunisation against COVID-19 is recommended for all people aged over 5 years and for immunocompromised children aged over 6 months.3

The service should ask all parents and carers to provide a copy of their child’s immunisation record when they enrol in the service. The Australian Immunisation Register maintains national records for all people vaccinated in Australia. The record is known as the ‘Immunisation History Statement’ and parents and carers can get a copy of the child’s statement from the Australian Immunisation Register. Check the statement and talk to the parents or carers about ensuring the child has received all the vaccinations recommended for their age group.

It is a good idea to check the National Immunisation Program Schedule and your state or territory health department’s website regularly (for example, once a year) for any changes to the immunisation schedule.

Children who are not fully immunised

Children may be defined as not fully immunised because they:

- have not received any vaccinations under the National Immunisation Program Schedule

- have not received all recommended doses of a vaccine appropriate to their age according to the National Immunisation Program Schedule

- have only been naturopathically or homeopathically vaccinated (this is sometimes called ‘not medically vaccinated’). This is because naturopathic or homeopathic vaccinations are not effective.

Under the national No Jab No Play, No Jab No Pay legislation, for a family to receive family tax benefits or fee assistance, the children must be fully immunised or have a medical reason certified by an approved immunisation provider not to be immunised or not to have certain vaccines.

Additionally, in some jurisdictions, children must be fully immunised or have a medical reason not to be immunised to attend education and care services. Check the No Jab No Play, No Jab No Pay legislation for the rules in your state or territory.

If children who are not fully immunised are able to attend education or care services in your state or territory, they should still be excluded from the service during outbreaks of some infectious diseases (such as measles and whooping cough), following advice from your local public health unit. Discuss with the parent or carer that their child may need to be excluded during such events, even if their child is well, because they may be at risk of infection.

The service’s immunisation policy should clearly describe rules around immunisation and exclusion (see Involving parents and carers in section 4.3).

Encourage immunisation

Encourage parents and carers to immunise their children by:

- putting up wall charts about immunisation in rooms

- putting a message about immunisation at the bottom of receipts and newsletters.

When enrolling children, education and care services should ask for immunisation records and make a note of when the child will need updates to their vaccinations. At least annually, check for children who are behind in their vaccinations, discuss with their parents or carers and update their records. The child may need ‘catch-up’ vaccinations to get up to date – you can suggest parents and carers talk to their child’s doctor about a catch-up schedule.

Refer parents and carers to their doctor, the Australian Immunisation Handbook and the No Jab No Play, No Jab No Pay legislation if they have any concerns.

Managing symptoms after vaccination

Vaccinations can cause several common side effects in the hours and days after vaccination, which you may see in children in your care. These are usually mild and do not last long. Treatment is not usually needed.

The Australian Immunisation Handbook provides an up-to-date comparison of the effects of diseases and the side effects of vaccines on the National Immunisation Program.

Managing injection site discomfort

Many vaccine injections can cause soreness, redness, itching, swelling or burning at the injection site for 1–2 days. Paracetamol can ease this discomfort. Sometimes a small, hard lump may persist for weeks or months. This should not cause concern and does not need treatment.

Managing fever after vaccination

If a child develops a fever after a vaccination, give them extra fluids to drink and do not overdress them if they are hot. It is not generally necessary to give children paracetamol or ibuprofen at the time of vaccination, but it may be needed if a child has a fever and discomfort afterwards. Check that the parent or carer has given permission for their child to be given medication. Follow the instructions on the label carefully.4

If a child is sick after vaccination, monitor them carefully (see section 4.1 If a child is sick). They may be sick because of another condition.

Immunisation for adults

It is vital that educators and other staff are up to date with their vaccinations

Immunisation protects not only staff, but also the children they work with, who may be highly vulnerable to vaccine-preventable disease.5 Regularly check the National Immunisation Program Schedule and your state or territory health department’s website for any changes to the vaccinations available for adults.

All educators and other staff should be vaccinated according to the recommendations in the Australian Immunisation Handbook. This includes additional vaccines recommended for people at occupational risk, including those working in children’s education and care.

This is based on the Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare, which recommend:

‘that all healthcare workers to be vaccinated in accordance with the recommendations for healthcare workers in the Australian Immunisation Handbook. Note: The advice reflects recommended practice supported by strong evidence. Healthcare facilities must also consider relevant state, territory and/or Commonwealth legislation regarding mandatory vaccination programs for healthcare workers’.

Service requirements

Approved providers and service leaders have a duty of care to ensure the workplace health and safety of educators, other staff and others in the workplace such as children, parents and carers, as far as is reasonably practical. This includes managing their risk of exposure to diseases that can be prevented by immunisation and other infection control practices. Immunisation of educators and other staff is an effective way to manage the risk of exposure because many diseases are infectious before the onset of symptoms.

Employers should:

- develop a staff immunisation policy, in consultation with staff, that states the immunisation requirements for educators and other staff

- require all new and current staff to provide a copy of their Immunisation History Statement, which is available from the Australian Immunisation Register, and update as required

- provide staff with information about vaccine-preventable diseases – for example, through in-service training and written material, such as fact sheets

- refer staff to the Australian Immunisation Handbook for further information, or to their general practitioner to discuss any concerns they have about vaccination

- take all reasonable steps to encourage staff who are not vaccinated according to the National Immunisation Program to be vaccinated. Advice given to educators and other staff, and any refusal to comply with vaccination requests, should be documented.

If any educators and other staff are not vaccinated according to the National Immunisation Program, they increase the risk that children – especially infants – may be infected with a vaccine-preventable disease.

If educators or other staff refuse reasonable requests for vaccination, there may be consequences for their employment. All staff should be advised of potential consequences. These include:

- being restricted to only working with children over 12 months old

- having to take antibiotics during outbreaks of specific bacterial diseases that are vaccine preventable, even if the educator is not sick – this would be at the direction of your local public health unit

- being excluded from work during outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.

Recommended vaccinations for staff

Some occupations are associated with an increased risk of some vaccine-preventable diseases. The Australian Immunisation Handbook recommends that all people who work in children’s education and care are vaccinated against:

- whooping cough (pertussis) – Whooping cough vaccination using a dTpa vaccine is especially important for educators and other staff who care for children who are too young to receive all their recommended whooping cough vaccines. Even if the adult was vaccinated in childhood, booster vaccination is necessary because immunity to whooping cough decreases over time.

- measles, mumps and rubella – Measles–mumps–rubella (MMR) vaccination is important for educators and other staff born during or since 1966 who do not have vaccination records of 2 doses of the MMR vaccine, or do not have evidence of immunity to measles, mumps and rubella (a blood test can check immunity).

- chickenpox (varicella) – Chickenpox vaccination is important for educators and other staff who have not previously had chickenpox (a blood test may be required to confirm previous infection).

- hepatitis A – Hepatitis A vaccination is important because children can be infectious even if they are not showing symptoms.

- COVID-19 – All staff should be up to date with COVID-19 vaccinations and boosters. The Australian Immunisation Handbook provides COVID-19 vaccination recommendations for all age groups.

- flu (influenza) – Annual flu vaccinations are important because young children are at higher risk of serious complications from flu. Some staff may be eligible for a free flu vaccine because of pregnancy, older age or underlying conditions. They should check their state or territory health department website for further information.

Additional vaccinations are recommended for educators and other staff who work with specific groups, or who live in particular locations:

- hepatitis B – Educators and other staff who care for children with developmental disabilities should have hepatitis B vaccinations. Vaccination of the children should also be encouraged.

- Japanese encephalitis – Educators and other staff who work in areas of Japanese encephalitis transmission should be vaccinated against it. Ask your local public health unit for current recommendations.

Educators and other staff who are pregnant or immunocompromised (that is, who have a weakened immune system either from a disease or treatment) should seek advice from their doctor about vaccinations. Some vaccinations are recommended in immunocompromised people and to protect both mother and baby in pregnancy, while others are not recommended.

Scenario 2.1

There were several cases of COVID-19 in the education and care service. Alex, an educator, became sick several days after the first case was diagnosed. She had to take time off work to recover. Alex checked the state health department website to find the most up-to-date recommendations for people who are sick with COVID-19. There were no exclusion recommendations, so Alex referred to her service policy, which stated she could return to work when her symptoms had resolved.

Points to consider for Alex:

- COVID-19 is a vaccine-preventable disease – if Alex had been up to date with her vaccinations when she began working at the service, her chances of getting sick from COVID-19 would have been much smaller. Not catching COVID-19 would have saved her time and money, because she would not have had to take time off.

Points to consider for the service:

- All education and care service employers should have accurate records of their staff members’ immunisations and when any boosters are due, and should review these records regularly to keep them up to date.

- Every education and care service should have a clear policy about immunisations for staff and make sure that all staff are aware of this policy.

- When an outbreak occurs, service management can remind educators and other staff and parents and carers of the service’s policy on COVID-19 infections and where to find further information.

2.2 Hand hygiene

Hand hygiene is a general term that refers to any action that cleans hands, such as washing hands with soap and water then drying hands, or using hand sanitiser.

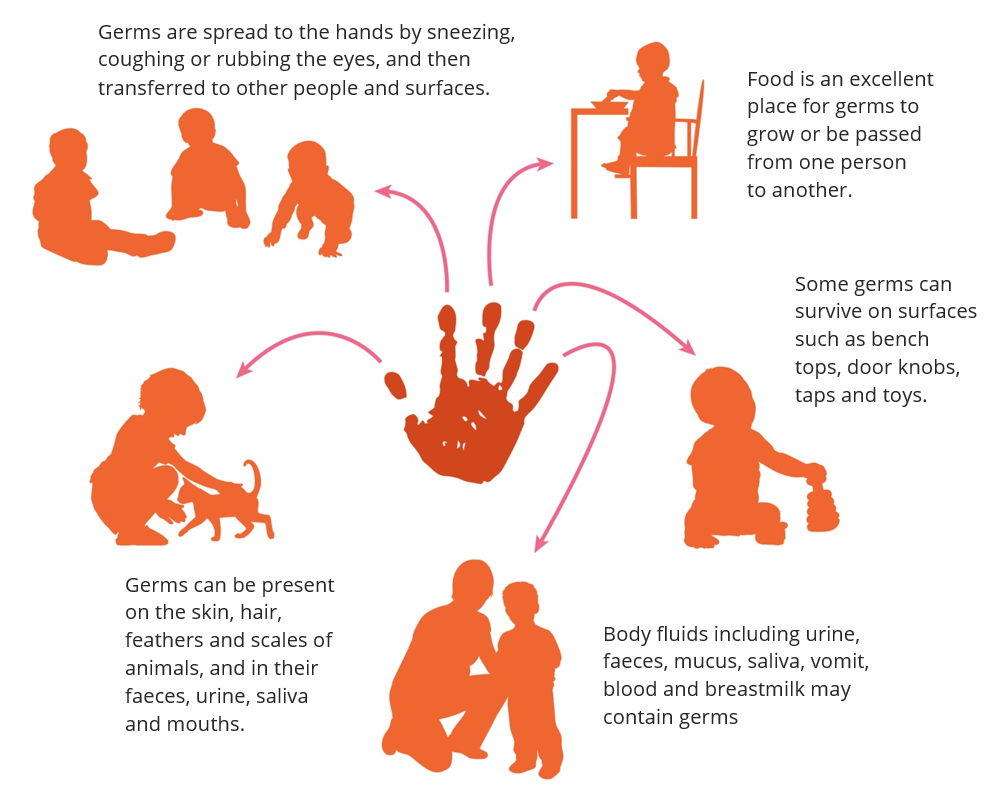

Many harmful germs can spread easily to other people or onto surfaces via contaminated hands. Hands are an important step in several chains of infection including direct contact, indirect contact, animals and food (Figure 2.1). Effective hand hygiene can break all these chains of infection.

Effective hand hygiene is important for everyone in the education and care service to help prevent disease.6 Hand hygiene for children also helps them to develop good hygiene habits. For younger children, you may need to wash or sanitise their hands or help them wash or sanitise their own hands.

Hand hygiene has no negative effects on overall health. Regular hand hygiene does not weaken immune systems or interfere with normal development of a child’s immune system.7

When to do hand hygiene

All educators and other staff and children should do hand hygiene regularly.

Think about the chain of infection when you think about hand hygiene. Perform hand hygiene before touching anything that should stay clean (such as before eating or preparing food) and after touching anything that might contaminate hands (such as after using the toilet or wiping a child’s nose).

Examples of when educators and other staff and children should perform hand hygiene are shown in Table 2.1.

| Who | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Educators and other staff |

|

|

| Children |

|

|

How to do hand hygiene

Hand hygiene can be done using soap and water, or hand sanitiser.

With soap and water

Washing hands with soap and water is the best option if you have visible dirt, grease or food on your hands.

Washing your hands with soap and running water loosens, dilutes and flushes off dirt and germs. Soap alone cannot remove dirt or kill germs – it is the combination of running water, rubbing your hands and the detergent in the soap that helps loosen the dirt, remove the germs and rinse them off your skin.

Warm water is recommended because soap lathers (soaps up) better with warm water. However, soap and cold water can be used if warm water is not available.

You do not need to use antibacterial soap8 – any soap is effective for hand hygiene if used properly.

There are 5 steps to washing hands:

- Wet hands with running warm water.

- Apply soap to hands.

- Lather soap and rub hands thoroughly, including the wrists, the palms, between the fingers, around the thumbs and under the nails. If you wear rings or other jewellery on your hands, move the jewellery around your finger while you rub to ensure that the area underneath the jewellery is clean. Rub hands together for at least 20 seconds (for about as long as it takes to sing ‘Happy birthday’ twice).

- Rinse hands thoroughly under running water.

- Dry hands thoroughly (see Hand drying).

A diagram of washing hands with soap and water is available from the World Health Organization.

Hand drying

Effective hand drying after washing your hands with soap and water is just as important as thorough hand washing. Damp hands pick up and transfer more bacteria than dry hands.9 Drying your hands thoroughly also helps remove any germs that may not have been rinsed off. Make sure you dry under any rings or other jewellery, because they can be sources of future contamination if they remain moist.

Using disposable paper towel is preferable for hand drying in education and care services. Cloth towels, if used, should be used by one person (that is, not shared) and hung up to dry between uses. Cloth towels should be laundered regularly to reduce the risk of spreading harmful germs.

Warm air dryers can also be useful, but they take longer to dry hands than using paper towel, can only serve one person at a time, and are often not used for long enough to ensure dry hands.

With hand sanitiser

Hand sanitisers (also known as alcohol-based hand rubs, antiseptic hand rubs or waterless hand cleaners) can reduce the number of harmful germs on your hands and should contain 60–80% alcohol.

Hand sanitisers are recommended when your hands are not visibly dirty.10 Hand sanitisers are also useful when soap and water are not available, such as when in the playground or on excursion. However, even if your hands are visibly dirty, using hand sanitiser is better than not cleaning your hands at all.

There are 3 steps to using hand sanitiser:

- Apply the amount of hand sanitiser recommended by the manufacturer to palms of dry hands.

- Rub hands together, making sure you cover in between fingers, around thumbs and under nails.

- Rub until hands are dry (alcohol-based sanitisers are self-drying, so you do not need a paper towel or hand towel). This should take about 20 seconds.

A diagram of cleaning hands with hand sanitiser is available from the World Health Organization.

It is a good idea to place hand sanitiser at the entrance to the education and care service. This can help remind parents, carers and children (as well as educators and other staff) to have clean hands when they enter the service.

Hand sanitisers are safe to use as directed, but children may be at risk if they eat or drink the cleaner, inhale it or splash it into their eyes or mouth. Hand sanitisers should be kept well out of reach of children and only used with adult supervision.

Hand care

Skin that is intact (that is, has no cuts, scratches, abrasions, cracks or dryness) provides a barrier against germs. Frequent hand hygiene can cause some people’s skin to become damaged (known as dermatitis) and allow harmful germs to enter the body.

The most common form of dermatitis is irritant contact dermatitis. Symptoms include dryness, irritation, itching, cracking and bleeding. Symptoms can range from mild to severe. Irritant contact dermatitis is mainly due to frequent and repeated use of hand hygiene products – especially soaps, other detergents and paper towels – which dry out the skin.

Allergic contact dermatitis is rare and is caused by an allergy to one or more ingredients in a hand hygiene product.

Hand hygiene products containing ingredients that soothe, moisturise or soften the skin (emollients) are readily available and can reduce irritant contact dermatitis.11 Hand sanitisers contain moisturisers, so can be gentler on the skin. Regularly moisturising hands can also help reduce dryness and irritation.

To avoid causing or increasing dermatitis:

DO

- use warm (not hot) water for hand washing

- wet hands before applying soap

- use moisturiser if you are prone to dry skin

DO NOT

- use products containing fragrances and preservatives

- wash hands with soap and water immediately before or after using hand sanitiser

- put on gloves while hands are still wet from hand washing or using hand sanitiser

- use rough paper towels to dry your hands.

When buying hand sanitisers, soaps and moisturising lotions for the service, make sure they are chemically compatible. This will minimise skin reactions and ensure that the hand hygiene products work effectively together. It is a good idea to buy hand hygiene and hand care products from a range made by a single manufacturer, because this may help to ensure that the products are compatible. If you have a materials supplier, speak to them for advice on chemically compatible products.

Educators and other staff with significant skin problems may be at higher risk of infection. If an educator or other staff member has significant skin problems, they should see their doctor.

2.3 Respiratory hygiene

Respiratory hygiene is about limiting airborne germs and the transmission of respiratory diseases.

Coughing and sneezing

Many harmful germs can be spread through the air (see Spread in section 1.1). By covering your mouth and nose when you cough or sneeze, you reduce how far the germs travel and stop them from reaching other people and contaminating surfaces.

In the past, people were encouraged to cover their coughs and sneezes with their hands. But if you do not clean your hands immediately, germs stay on your hands and can be transferred to any surfaces you touch.

The correct way is to cough or sneeze into your inner elbow or use a tissue to cover your nose and mouth. Put all used tissues in the rubbish bin straight away and clean your hands with either soap and water or hand sanitiser.

Mucus

If someone is sick, their mucus (snot) can contain harmful germs, even if they do not have a runny nose.

Hand hygiene after every time you wipe a child’s nose will reduce the spread of colds and other diseases.

It is not necessary to wear gloves when wiping a child’s nose. If you do wear gloves, you must remove your gloves and wash your hands or use hand sanitiser afterwards.

Dispose of used tissues and gloves immediately.

2.4 Wearing gloves and masks

Physical barriers, such as gloves and masks, can help prevent the transmission of germs.

Gloves

Gloves provide a protective barrier against germs. Using gloves correctly reduces the spread of harmful germs, but does not eliminate it completely.

If gloves are not used correctly, they can spread germs and put others at risk. When a person wears gloves, they may come into contact with germs which can then be transferred to other objects or their face.

Types of gloves

Disposable (that is, single-use only) gloves are made of nitrile, natural rubber latex or vinyl.

- Nitrile gloves are recommended for education and care services. They must be used by educators and other staff who have latex allergies, or with children who have latex allergies.

- Latex gloves are not recommended because they cause skin dermatitis, asthma and other allergies in children, educators and other staff. If no other gloves are available and latex gloves are used, powder-free gloves should be used, because powdered gloves may further contribute to latex allergies in children, educators and other staff.12

- Vinyl gloves are not recommended.13

Utility (reusable) gloves are made of heavy-duty rubber and should be worn during general cleaning activities.

When to wear gloves

Gloves prevent contamination of the hands and exposure to damaging substances.

Wear disposable gloves if you are likely to come in contact with body fluids – for example, when changing wet or dirty nappies or cleaning up vomit or blood. However, it is not necessary to wear gloves when wiping noses.

Wear utility gloves when using damaging chemicals or cleaning.

Table 2.2 shows when you should wear disposable gloves and when you should wear utility gloves.

Hand hygiene before and after wearing gloves

Wearing gloves does not replace the need to clean your hands, and you should do hand hygiene before putting gloves on and after taking them off.

Do hand hygiene before putting on gloves so that you remove as many harmful germs as possible from your hands. Otherwise, when you reach into the box of gloves, you can contaminate the other gloves in the box.

When you have finished a procedure that requires you to wear gloves, remove the gloves and clean your hands thoroughly. This is important because:

- any germs on your hands may have multiplied significantly while you were wearing the gloves

- there may be tiny tears or holes in the gloves that can allow germs to contaminate your skin

- you may contaminate your hands with the dirty gloves when taking them off.

Using disposable gloves

Never reuse or wash disposable gloves. They must be thrown away as soon as you have finished the activity that requires gloves.

Always clean your hands before and after wearing disposable gloves. Wear gloves on both hands.

If you have cuts or sores, cover these with a waterproof dressing before putting on disposable gloves.

Remember that the outside of the glove is dirty and the inside of the glove is clean. Avoid touching the inside of a glove with the outside of another glove and avoid touching bare skin or clean surfaces while wearing or removing contaminated gloves.

How to remove disposable gloves:

- Pinch the outside of one glove near the wrist and peel the glove off so it ends up inside out.

- Keep hold of the peeled-off glove in your gloved hand while you take off the other glove. Put 1 or 2 fingers of your ungloved hand inside the wrist of the other glove. Peel off the second glove from the inside, and over the first glove, so you end up with the 2 gloves inside out, one inside the other.

- Put the gloves in a plastic-lined, hands-free lidded rubbish bin and clean your hands. If such a bin is not available, put the gloves in a bucket or container lined with a plastic bag, then tie up the bag and take it to the outside garbage bin.

Illustrations of how to remove disposable gloves safely are available from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Masks

Masks reduce transmission of respiratory viruses, especially in crowded, poorly ventilated spaces. However, masks can be uncomfortable to wear for a long time. There is also a concern that mask use prevents children from learning to identify human facial expressions.

For these reasons, masks are not generally recommended for use in education and care services. However, masks may be mandated or recommended by public health authorities if there is an outbreak of certain diseases (see section 4.5 Disease outbreaks). Keep up to date with any requirements in your state or territory.

There are 2 types of masks:

- Surgical masks prevent transmission of larger droplets and reduce contact of potentially contaminated hands with the mouth and nose. In general, education and care services should use surgical masks (if masks are required). These masks are not air filters and do not stop transmission of small particles – when you breathe while wearing a surgical mask, air leaks around the sides. For this reason, surgical masks are useful to prevent the spread of germs spread by droplets (for example, flu, common cold) but not germs spread through contaminated air.

- P2/N95 respirators (often referred to as masks) provide a stronger seal around the mouth and nose and are made of less-porous material. They filter out the very small particles that carry germs spread by contaminated air (for example, measles, chickenpox and COVID-19). Respirators are not usually required in education and care services, but educators and other staff may be directed to use them in an outbreak of one of these diseases.

Other protective equipment

Face shields and protective eyewear (including goggles and safety glasses) are usually not required in education and care services.

Some education and care services may recommend protective equipment in some circumstances. For example, protective eyewear may be recommended if there is a risk that droplets or splashes of body fluids may go into the eyes of educators or other staff. This can occur when managing nosebleeds, dental injuries or bleeding wounds.

Public health units may also recommend the use of protective equipment in some circumstances (for example, during a disease outbreak).

2.5 Nappy changing and toileting

Faeces (and sometimes urine) contain billions of harmful germs such as bacteria and viruses. Hygienic nappy changing and toileting prevents these germs from spreading disease to staff and other children.

Children in education and care services may have disposable or cloth nappies. Either can be used safely, if you follow appropriate care and cleaning procedures. Both cloth and disposable nappies should be waterproof – either through the inclusion of a waterproof layer, or the use of a separate waterproof cover. Use flushable, disposable liners with cloth nappies.

Correct storage and disposal of nappies is also critical to preventing the spread of harmful germs

Nappy changing

Infection control practices should be used when children’s nappies are changed. Infection control practices include hand hygiene and proper cleaning and disinfection procedures (see the Glossary).

Change nappies when they have faeces in them, and at routine intervals throughout the day. This will minimise the amount of time that urine and faeces are in contact with the child’s skin.

Wash your hands or use hand sanitiser:

- before preparing the nappy change area

- after changing the nappy

- after cleaning the nappy change area.

Nappy changing procedure

Preparation:

- Bring your supplies to the changing area. This includes a clean nappy, wipes, baby cream labelled with the child’s name (if applicable), gloves, a plastic or waterproof bag for soiled clothing, and extra clothes.

- Do hand hygiene. It is very important to wash your hands or use hand sanitiser when changing a nappy, even if you are going to use gloves. This is so that when you have finished changing the child, you can remove the dirty gloves and dress the child without needing to interrupt the nappy changing procedure to clean your hands before dressing the child.

- Put on disposable gloves. This is recommended because educators and other staff are likely to come into contact with body fluids including urine and faeces during nappy changes. Follow your service’s policies and procedures.

- Place paper towel or plain paper on the change table, if desired, to reduce mess.

- If the child can walk, walk with them to the changing area. If the child cannot walk, pick them up and carry them to the changing area. If there are faeces on the child’s body or clothes, hold the child away from your body if you need to carry them.

Changing:

- Place the child on the change table and unfasten the nappy.

- Clean the child’s bottom with disposable nappy wipes. Always wipe front to back.

- For disposable nappies, place dirty wipes in the nappy, remove the nappy from the child and put it in a plastic bag. Place the bag in the designated bin. For cloth nappies, put the disposable liner and wipes in the designated bin. Put the used nappy in a plastic bag and put it in the sealed container that you have for that child.

- Remove the paper from the change table and put it in the designated bin.

- Remove your gloves and dispose of them so you will not touch the clean child with dirty gloves. For details on how to remove gloves properly, see Using disposable gloves in section 2.4.

- If a child requires nappy cream, clean your hands (if safe to do so, for example, using accessible hand sanitiser), put on new disposable gloves and apply the cream. Remove the gloves and dispose of them.

- Place a clean nappy under the child and fasten the nappy.

- Dress the child.

- Wash your hands and the child’s hands before placing the child back into a supervised area. (The standard recommendation is to clean hands after removing gloves. But when changing a nappy, it is more important to keep the child safe from falling and finish the nappy change before cleaning your hands.)

Cleaning:

- After every nappy change, clean the nappy change surface (see Nappy change area in section 3.2 for details on the best methods of cleaning for this area). If body fluids have got on the surface, clean then disinfect the surface.

- Wear utility gloves for the cleaning. Do hand hygiene using soap and water or hand sanitiser. If your hands are visibly dirty or you have just removed gloves, wash your hands with soap and warm water.

Nappy change area

It is important to have a separate, dedicated nappy change area that is positioned away from the food preparation area and close to a warm water tap, sink and paper towels.

The supplies you need should be ready and within reach. The nappy change area should have baby wipes, clean nappies, disposable gloves, baby cream labelled with the child’s name (if applicable), paper for the change table, and storage for used nappies and for soiled clothes.

Nappy change surface

The nappy change surface may be a change mat or a waterproof sheet over a mattress on a change table. Ensure that the nappy change surface is:

- waterproof

- in good condition

- smooth and easily cleaned (germs can survive in cracks, holes, creases, folds and seams)

- cleaned after every nappy change.

It is a good idea to change surfaces during the day to help prevent spread of germs. For example, you can have 2 change mats and swap them, or cover a change mat with a waterproof sheet and remove it halfway through the day.

If possible, do not share the same nappy change surface with children from another room. Having separate change mats for each room can help limit the spread of an infection and contain it to a single room. If this is not possible, take extra care to ensure that the change mat is thoroughly cleaned after each nappy change, especially if a child is known to have an infection (see Nappy change area in section 3.2).

Nappy change paper

It is a good idea to use disposable paper on the nappy change surface during nappy changes. Every time a child has their nappy changed, germs get onto the change surface. Placing paper on the surface before you place the child prevents many of these germs from reaching the surface itself.

Any type of new, clean, plain paper that can absorb leaks can be used for this (for example, paper towel or large sheets of paper). Remove the paper in the middle of the nappy change, before putting the child’s clean nappy and clothes on, and put the paper and the germs in the bin.

If an education and care service does not wish to use paper on the change table, educators and other staff must take extra care when cleaning the change mat between nappy changes. Even when using paper, the nappy change surface must be cleaned after each nappy change.

Nappy storage and disposal

Always store and dispose of soiled nappies correctly to minimise the spread of harmful germs.14

Keep soiled nappies in a waterproof container that can contain smells. Do not keep containers for soiled nappies in areas used for preparing or eating food, or where children play.

For disposable nappies:

- Remove the nappy.

- Put the dirty nappy in a plastic bag and tie the bag.

- Put the bag in a designated bin that is used only for used nappies. The bin should have a lid and be lined with a plastic bag.

For cloth nappies:

- Put the flushable, disposable nappy liner in the toilet.

- Remove the nappy.

- Do not rinse the nappy; put it in a plastic bag and tie the bag.

- Put the bag in a sealed container, which can be a lidded bucket or ‘wet bag’. Have one container for each child who is using cloth nappies, marked with the child’s name. Keep the container where it can be securely left for the child’s parent or carer to collect it.

Waste management for disposable nappies:

- Have lined bins in the nappy changing areas.

- Do not overfill bins – when they are three-quarters full, tie the lining bag up and put it into the main waste bin.

- Have a schedule for emptying the bins during the day and at the end of the day.

- Clean all bins according to the specified cleaning schedule.

- Wear disposable gloves when collecting waste and emptying bins.

- When you are finished, remove gloves and do hand hygiene.

Learning to use the toilet

Ask parents or carers to supply a clean change of clothing for all children, including those who are learning to use the toilet. If a child has got faeces on their clothes, dispose of faeces in the toilet and place the soiled clothes in a plastic bag. Keep these bags in a designated place until the parent or carer can take them home that day.

For children who are learning to use the toilet:15

- Help the child use the toilet (potty chairs are not recommended because they increase the risk of spreading infection).

- Encourage children, especially girls, to wipe front to back, to reduce the chance of introducing bowel bacteria to the urinary tract.

- After they have finished toileting, guide younger children to the handwash basin and help them wash their hands.

- Supervise older children while they wash their hands.

- Explain to the child that washing their hands and drying them properly will stop germs that might make them sick.

- Always do your own hand hygiene after helping children use the toilet.

2.6 Safely dealing with wounds and body fluids

Education and care services routinely deal with wounds and body fluids including urine, faeces, mucus, saliva, vomit, blood and breastmilk.

Follow your service’s procedures to safely deal with body fluids, and to help prevent spills. You will also need to know how to safely deal with any spills (see How to clean spills of body fluids in section 3.2).

Wounds

Children must be supervised at all times to ensure they play safely. If a child is bleeding from an injury, nosebleed or bite from another child, you must:

- look after the child

- dress the wound (if needed) ‒ this should be done by someone with approved first aid training

- check that no-one else has come in contact with the blood

- clean up the blood.

In an emergency, call 000 for an ambulance. If the situation is not urgent, follow the service’s procedures about notifying the parent or carer.

Looking after the child

- Avoid contact with the blood.

- Comfort the child and move them to safety, away from other children.

- Put on gloves, if available.

- Apply pressure to the bleeding area with a bandage or paper towel.

- Elevate the bleeding area, unless you suspect a broken bone.

- When the wound is covered and no longer bleeding, remove your gloves, put them in a plastic bag or alternative, seal the bag and place it in the rubbish bin.

- Wash your hands thoroughly with soap and running warm water.

If at all possible, do not touch the wound if you do not have gloves. If you do not have gloves, get someone wearing gloves to take over from you as soon as possible. Then wash your hands and go back to your other duties.

It is a good idea to wear a face shield or protective eyewear if there is a chance that blood could enter your eyes or mouth (for example, if the child has a mouth wound and is coughing).

Dressing the wound

- Put on gloves, if there is time.

- Dress the wound with a bandage or suitable substitute and seek assistance.

- Remove your gloves, put them in a plastic bag, seal the bag and place it in the rubbish bin.

- Wash your hands thoroughly with soap and running warm water.

Checking for contact with blood

Ask the adults and children near the spill if they have come into contact with the blood. For infants and non-verbal children, check if they have come into contact with the blood.

If they have, remove any blood from the person with soap and water and make sure they wash their hands thoroughly.

Body fluids

Strategies to prevent spills of body fluids include:

- regularly toileting children (changing their nappy or taking them to the toilet)

- excluding children with vomiting or diarrhoea

- encouraging children to blow their noses, especially any who have a runny nose, and disposing of tissues appropriately

- minimising the risk of injury by supervising and supporting children to play safely.

When a spill occurs, clean it up as soon as possible. If possible, place a safety sign around the spill to keep people away until it can be cleaned.

When cleaning up a spill of blood, faeces, urine, vomit or breastmilk, wear gloves and wipe up the spill with paper towels. Next, clean the surface with warm water and detergent, and dry with paper towels. Wipe the area with disinfectant and allow to dry.

Wash your hands thoroughly with soap and running warm water after you have cleaned any spills of body fluids.

Staff wound hygiene

Use waterproof dressings to cover open cuts or sores on the skin.

The skin is a natural barrier that stops germs entering the body. When the skin is damaged, germs can enter and lead to infections at the site of the cut or through the rest of the body. Placing a waterproof dressing (like an adhesive plastic strip) over the cut stops germs from entering the cut and helps the skin heal more quickly.

See also Hand care in section 2.2 for tips on how to prevent skin irritation.

2.7 Contact with animals

Animals can be a source of joy and stimulation for children. However, all animals carry germs that can cause infections if a person is bitten or scratched. Animal faeces also carry germs.

Contact with animals can spread disease. Germs are present on the skin, hair, feathers and scales of animals, and in their faeces, urine and saliva. These germs may not cause disease in the animal, but they may cause disease in humans. Some harmful germs can multiply in insects such as mosquitoes, fleas and ticks and spread through the insect’s bite. Insects that carry germs are known as disease ‘vectors’.

Animals

Some simple measures will minimise the health risk from contact with animals:

- Hygiene and child care

- Make sure that adults and children wash their hands with soap and water (or use hand sanitiser if soap and water are not available) after touching animals or cleaning an animal’s bedding, cage or tank.

- Supervise children when they have contact with animals. Do not allow children to play with animals while they or the animals are eating. Do not let children put their faces close to animals.

- Animals and animal care

- Choose appropriate animals. Avoid keeping ferrets, reptiles (including lizards, iguanas, snakes and turtles) and parrots. This is because these animals can carry germs that can be dangerous to humans (for example, reptiles often carry Salmonella).

- Ensure that animals are free of fleas, mites, worms and skin diseases. Animals should be immunised as appropriate. Animals that are sick should be treated promptly by a veterinarian and kept away from children until the animal is well an animal that is irritable because of pain or disease is more likely to bite or scratch.

- Do not allow animals in sandpits, and do not allow them to urinate or defecate on soil, in pot plants or in vegetable gardens.

- Cleaning

- Always wear gloves when handling animal faeces, emptying litter trays and cleaning cages.

- Dispose of animal faeces and litter daily. Place faeces and litter in a plastic bag or alternative and put it out with the rubbish.

- Pregnant women, in particular, must avoid contact with cat faeces to minimise their risk of toxoplasmosis (see Toxoplasmosis fact sheet).

- If you have a birdcage, wet the floor of the cage before cleaning it to avoid inhalation of powdered, dry bird faeces.

Insects, spiders and ticks

Education and care services should try to prevent insects (especially flies and mosquitoes) and arachnids (spiders and ticks) from entering indoor areas. Screening windows and doors is a key way to prevent insects from entering. Barrier sprays can also be used. Remove or kill (with an appropriate spray or swatter) any insects or arachnids that come in.

If a child is bitten by an insect or arachnid while in care, monitor them for any reaction or illness and treat appropriately.

- If there is an allergic reaction or you know the child is allergic to the type of bite (for example, bees or ticks), contact the parent or carer and seek medical care if needed.

- If the child is bitten by an insect and there does not seem to be a reaction, let the parent or carer know about the bite at pick-up.

- If a child is bitten by a spider, contact the parent or carer and seek medical care if needed.

- For tick bites where the tick is still embedded in the child’s skin, kill and remove the tick using an ether spray (see the healthdirect recommendations).

Fleas can infest animals and humans, and flea bites cause skin irritation and inflammation. Treat animals, their bedding (that is, where they usually rest) and their immediate environment with a flea treatment to kill adult and immature fleas. Always follow the manufacturer’s instructions.

Bats

Australian bats may carry a lyssavirus that is very similar to the rabies virus. Treatment of bat bites or scratches can require several vaccine injections and injection of protective antiserum into the wound area.

Lyssavirus can be transmitted to humans through direct contact with bats. Do not approach or handle bats, including sick or injured animals, because there is a high likelihood of being scratched or bitten. Bats that are not in direct contact with people (for example, bats in trees) pose no risk of transmitting lyssavirus. Only trained and immunised wildlife handlers wearing suitable protective equipment should attempt to handle or move bats.

If you or a child is scratched or bitten by a bat, immediately clean the wound with soap and running water for 15 minutes and see a doctor or local hospital emergency department as soon as possible.

Fish and marine animals

Fish and fish tanks can carry harmful germs. If you need to reach into a fish tank, wear gloves or use a net. If you do use your bare hands and arms, wash your hands and arms thoroughly with soap and water afterwards. Never clean an aquarium in a kitchen sink or food preparation area. Use a laundry sink for cleaning and disposal of aquarium water.

Scratches from fish and marine animals, including coral, can cause unusual and serious infections. If an injury caused by a fish, or a wound contaminated by sea water, pond water or aquarium water, looks like it may have become infected, see a doctor promptly and explain how the injury occurred.

Scenario 2.2

You have invited a local reptile zoo to provide an interactive reptile show for the children at your service as part of an end-of-year celebration. The reptile show will include a group presentation to educate children and increase their awareness about reptiles and a chance for children to touch some of the reptiles. The celebration will conclude with a barbecue lunch. The reptile zoo is bringing 2 staff members to conduct the presentation and interactive show.

On the morning of the celebration, Sasha’s mum calls to advise that Sasha has a sore throat and a mild cough and will not be attending the service that day. Sasha’s mum asks if Sasha can attend for the reptile show only and then go home.

Actions to take:

- Advise Sasha’s mum that it is best for Sasha to stay home because she has symptoms of a respiratory disease.

- Refer to the Respiratory symptoms fact sheet and offer to email a copy to Sasha’s mum.

- Make sure the reptile display is set up in a section of the service that is away from the food preparation area.

- Make sure that all children, educators and other staff, parents and carers do hand hygiene before and after touching animals. Have hand sanitiser available during the interactive session.

- Supervise children when they touch the reptiles. Separating the children into small groups may make this easier.

- Make sure all children and adults do hand hygiene at the end of the activity and before the barbecue lunch begins.

2.8 Protecting pregnant staff and visitors

Educators and other staff who are pregnant, as well as pregnant visitors to the service such as family members, should be aware of how some infections can affect an unborn child. If a staff member is pregnant, it is even more important than usual for the education and care service to make sure that all staff follow good infection control practices.16

The diseases listed in Table 2.3 can cause pregnancy risks and may occur in education and care services. Risks vary depending on the disease.

For most diseases, good hand and respiratory hygiene are the main ways to prevent infection, and wearing gloves and masks may be useful in some cases. Immunisation is also effective and recommended for protection against some diseases. For some diseases, pregnant staff or visitors may need to avoid exposure.

If any of these diseases occur in the education and care service, alert pregnant staff and visitors so they can take precautions. Seek advice from local public health authorities if you are concerned about risks to pregnant staff and visitors from an infectious disease diagnosed in a child or staff member.

For more information about these diseases, see the relevant fact sheets. If a case of the disease occurs in the service, provide a printout of or a link to the fact sheet to all pregnant staff members and all families. Advise them to seek medical advice if they have concerns.

References

1 Department of Health and Aged Care (2018). Fundamentals of immunisation, in the Australian Immunisation Handbook, Australian Government, Canberra.

2 ATAGI (Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation) (2022). Statement on the administration of seasonal influenza vaccines in 2022, Australian Government, Canberra.

3 Department of Health and Aged Care (2023). COVID-19, in the Australian Immunisation Handbook, Australian Government, Canberra.

4 MedicineWise (2022). Treating my child’s pain or fever – paracetamol or ibuprofen? National Prescribing Service, Canberra.

5 Department of Health and Aged Care (2022). About immunisation, Australian Government, Canberra.

6 Staniford LJ & Schmidtke KA (2020). A systematic review of hand hygiene and environmental disinfection interventions in settings with children, BMC Public Health 20:195; Luby SP, Agboatwalla M, Feikin DR, Painter J, Billheimer W, Altak A & Hoekstra RM (2005). Effect of handwashing on child health: a randomised controlled trial, Lancet 366(9481):225–223.

7 Rook GAW & Bloomfield SF (2021). Microbial exposures that establish immunoregulation are compatible with targeted hygiene, Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 148(1):33–39; Bloomfield SF, Rook GA, Scott EA, Shanahan F, Stanwell-Smith R & Turner P (2016). Time to abandon the hygiene hypothesis: new perspectives on allergic disease, the human microbiome, infectious disease prevention and the role of targeted hygiene, Perspectives in Public Health 136(4):213–224.

8 Hand Hygiene Australia (2022). FDA ruling on over-the-counter antibacterial soaps, HHA, Melbourne.

9 Huang C, Ma W & Stack S (2012). The hygienic efficacy of different hand-drying methods: a review of the evidence, Mayo Clinic Proceedings 87(8):791–798.

10 Hand Hygiene Australia (2022). Alcohol-based handrubs, HHA, Melbourne.

11 Hand Hygiene Australia (2022). Hand care issues, HHA, Melbourne.

12 National Health and Medical Research Council (2023). Australian guidelines for the prevention and control of infection in healthcare, NHMRC, Canberra.

13 Rego A & Roley L (1999). In-use barrier integrity of gloves: latex and nitrile superior to vinyl, American Journal of Infection Control 27(5):405–410.

14 Health Protection Scotland (2018). Infection protection and control in childcare settings, NHS National Services Scotland, Glasgow.

15Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority (2016). Toileting and Nappy Changing Principles and Practices, ACECQA, Canberra.

16 Radauceanu A & Bouslama M (2020). Risks for adverse pregnancy outcomes and infections in daycare workers: an overview of current epidemiological evidence and implications for primary prevention. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 33(6):733–756.