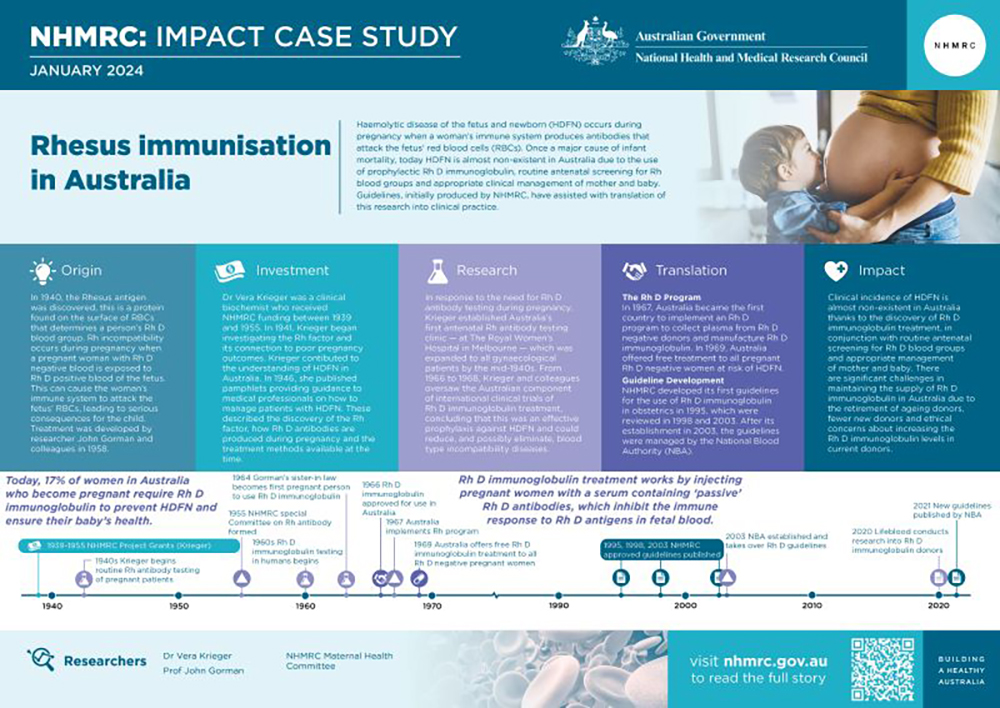

Haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN, also known as Rh Disease) can occur during pregnancy when a pregnant woman’s immune system produces antibodies that attack their fetus’ red blood cells (RBCs). Once a major cause of fetal and newborn mortality, today HDFN is almost non-existent in Australia due to routine antenatal blood grouping and antibody screening, and the use of prophylactic Rh D immunoglobulin and appropriate clinical management of mother and baby. Guidelines, initially produced by NHMRC on behalf of the Department of Health and Ageing, have assisted with translation of the research on Rh D antibody screening and Rh D immunoglobin into clinical practice.

Origin

The ABO blood group system was first described in 1901 and is determined by the presence or absence of specific antigens – A and B – on the surface of RBCs. In 1940 the Rhesus antigen was discovered. This is a protein on the surface of RBCs whose presence or absence determines a woman’s Rh D blood group and is unrelated to the ABO blood group. If the Rh D antigen is present, an individual will be Rh D positive and if it is absent, they will be Rh D negative. When combined with ABO blood groupings, a person who, for example is A positive, will have A antigens alongside the presence of Rh D antigens.

An antigen is any substance that causes the body to make an immune response against that substance. Antigens include toxins, chemicals, bacteria, viruses, or other substances that come from outside the body.2

Rh incompatibility occurs during pregnancy when a pregnant woman with an Rh D negative blood type is exposed to the Rh D positive blood of the fetus (inherited through an Rh D positive father’s sperm). Such exposure can occur during pregnancy, childbirth and miscarriage and can trigger the woman’s immune system to produce antibodies to attack the fetus’ Rh D positive RBCs. The first pregnancy with an Rh D positive fetus provides the primary stimulus for antibody development (sensitisation). If sensitisation occurs, subsequent pregnancies with Rh D positive fetus’ are at risk of HDFN.

HDFN occurs when antibodies cross the placenta into the fetus’ circulation and destroys the fetus’ RBCs which can lead to serious – and potentially fatal – consequences for the fetus. Without intervention, HDFN affects 1% of babies and is a significant cause of perinatal mortality and morbidity. Today, HDFN is largely preventable due to the development of Rh D immunoglobulin. This treatment works by injecting Rh D negative pregnant women with a serum containing ‘passive’ Rh D antibodies (also referred to as anti-D), which inhibit the immune response to Rh D antigens in fetal blood. This prevents the mother’s immune system from producing antibodies that attack the fetus’ RBCs and, in turn, reduces the risk of HDFN for subsequent pregnancies.

The development of this treatment was the result of an idea by US-based researcher John Gorman and colleagues in 1958. Encouraged by preliminary findings developed using male volunteers, Gorman tested Rh D immunoglobulin on his sister-in-law, who was Rh D negative and pregnant with an Rh D positive baby. The treatment was successful, and she went on to give birth to four more healthy children with the assistance of Rh D immunoglobulin injections.

Grants and Investment

Dr Vera Krieger was a clinical biochemist who received NHMRC funding between 1939 and 1955. In 1941, after the discovery of the Rh blood group, Krieger began investigating the Rh factor and its connection to poor pregnancy outcomes.

The PDF poster version of this case study includes a graphical timeline showing NHMRC grants provided and other events described in the case study.

Research

In response to the need for Rh antibody testing to determine if a pregnant woman and her unborn child were at risk of HDFN, Krieger developed Australia’s first antenatal Rh D testing clinic at The Royal Women’s Hospital in Melbourne. The clinic was expanded to offer routine Rh D antibody testing to all pregnant patients by the mid-1940s.3

Through her research and publications, Krieger made important contributions to the understanding of HDFN in Australia. In 1946, she published a number of pamphlets providing guidance to medical professionals on how to manage babies with HDFN. These described the discovery of the Rh factor, how Rh D antibodies are produced during pregnancy and the treatment methods available at the time, which involved blood transfusions for fetus’ or newborns with HDFN.2

From 1966 to 1968, Krieger and obstetrician Geoffrey Bishop oversaw the Australian component of international clinical trials of Rh D immunoglobulin. The trial results indicated that injections of plasma containing Rh D immunoglobulin prevented a Rh D negative woman from developing antibodies against Rh D positive RBCs. They concluded that Rh D immunoglobulin was an effective prophylaxis (preventative measure) against HDFN and could reduce – and possibly eliminate – this disease.4

The 1997 discovery of cell-free DNA in maternal blood has led to the establishment of services for non-invasive pre-natal testing (NIPT) for RHD fetal genotyping in specialised laboratories in Europe. Australian Red Cross Lifeblood (Lifeblood; funded by Australian governments) developed an assay for use in Australia, modelled on the testing service offered by the National Health Service Blood and Transplant in the UK.5,6 The test was validated for the Australian population by Lifeblood in collaboration with the Royal North Shore (NSW) and Mater Mothers’ Hospital (QLD). Lifeblood currently offers NIPT for fetal RHD in high-risk pregnancies.7

Translation

The Rh program

In response to Krieger’s work, in 1955, NHMRC appointed a special Committee of experts to advise on the desirability of including the determination of Rh D antibodies as part of routine testing during pregnancy. The Committee advised that:

- determination of ABO blood group and Rh status was an essential part of pre-natal care

- blood of Rh D negative women having their second or later pregnancies should be examined for Rh D antibodies at their first pre-natal visit and between the 34th–36th week.

In 1967, NHMRC’s Maternal Health Committee informed the Council that, 'there did not appear to be any possibility of producing sufficient anti-Rh gamma globulin from voluntary donors with naturally occurring antibodies to cope with the likely needs in the treatment of Rh incompatibility in pregnant women'.

The Committee noted that, to produce sufficient Rh D immunoglobulin, hyperimmunisation of donors should be considered. It recommended that the National Blood Transfusion Service be invited to consider this matter and coordinate the collection of suitable blood for production of anti-Rh gamma globulin by the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories (CSL).

In that same year, Australia became the first country to implement an Rh program8, a joint project by the Australian Red Cross and CSL. The program, which is still in operation today, involves collecting plasma from a small group of Rh D negative blood donors with anti-D antibodies, who had been previously exposed to the Rh D antigen during transfusion or pregnancy, or who were immunised for the purpose of producing this plasma.9 The plasma was then used to manufacture Rh D immunoglobulin, which was administered to treat Rh D negative women whose babies were at risk of Rh incompatibility.

In 1969, Australia became the first country to offer free Rh D immunoglobulin to all pregnant Rh D negative women at risk of HDFN.4

Guideline Development

In 1995, NHMRC established a working party to develop guidelines on the prophylactic use of anti-D in obstetrics. These guidelines were endorsed by the Council at its November 1995 session and published in 1996. In 1998, NHMRC’s Health Advisory Committee reviewed the guidelines and published a revised document entitled, Guidelines for the use of RhD immunoglobulin (Anti D) in obstetrics 1999, which was endorsed by the Council in March 1999.

The 1999 guidelines addressed the issue of a shortage of supply and recommended that the situation be carefully monitored and reviewed regularly, stating that routine antenatal prophylaxis should not be implemented until there was sufficient supply. In 2001, the NHMRC Working Party was reconvened to review and update the guidelines, given developments in the availability of Rh D immunoglobulin since the publication of the 1999 guidelines. A literature search was commissioned to update the evidence base for the guidelines, and the cost–effectiveness data were reviewed.

In 2003, the National Blood Authority (NBA) was established by the Australian Government and state and territory governments to manage the Australian blood sector and blood-related services. In that same year the NBA released a revised guideline for the use of Rh D immunoglobulin which was approved by NHMRC. The guideline included a strategy to enable the staged introduction of antenatal prophylaxis in the short term, while working towards self-sufficiency in the longer term.

In 2021, the NBA and the Royal Australian College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists released a new evidence-based guideline: the Guideline for the prophylactic use of Rh D immunoglobulin in pregnancy care. This guideline has recommendations and expert opinion points for health professionals on the appropriate use and timing of pathology tests to identify maternal and fetal Rh D status, and prophylactic Rh D immunoglobulin in Rh D negative pregnant women.

Health Outcomes and Impacts

Today, approximately 17% of women in Australia who become pregnant require Rh D immunoglobulin injections to prevent Rh disease and ensure their baby’s health.10 Clinical incidence of HDFN is almost non-existent in Australia due to the discovery of Rh D immunoglobulin in conjunction with routine antenatal screening for Rh blood groups and appropriate management of mother and baby.

Lifeblood has maintained the Rh program collecting plasma from donors with anti-D for more than 50 years. There continue to be significant challenges in maintaining the supply of Rh D immunoglobulin in Australia due to the retirement of ageing donors, fewer new donors (due to fewer women developing anti-D antibodies following pregnancy or transfusion) and ethical concerns about increasing the anti-D levels in current donors.5 In 2020, Lifeblood’s study to understand the motivators and barriers of recruiting and retaining anti-D donors found that they were highly motivated and dedicated to the program, and many had a personal connection to donating anti-D. The findings suggested that the current approach to recruitment could be broadened to include all donors who meet formal selection criteria, with retention enhanced by reinforcing and rewarding the motives for donating.11 Recruitment for new blood donors continues to be a high priority for Lifeblood.

Following a systematic review of evidence and consensus by a multidisciplinary committee, NIPT for fetal RHD blood group genotype for all Rh D negative pregnancies in Australia was recommended in the Guideline for the prophylactic use of Rh D immunoglobulin in pregnancy care. The introduction of targeted Rh D immunoglobulin prophylaxis based on results of NIPT for RHD testing after 11 weeks gestation, will allow approximately 14,000 pregnant women to avoid administration of the immunoglobulin, reducing healthcare costs and reducing demand for Rh D Immunoglobulin. More information about NIPT for fetal RHD can be found on the NBA website.

Researchers

Doctor Vera Krieger

Vera Krieger (1901-1992) obtained a Bachelor of Science (1924), Master of Science (1926) and Doctor of Science (1938) from The University of Melbourne. In 1928, she was appointed as the first Clinical Biochemist at The Royal Women’s Hospital but conducted her investigations in a nearby laboratory at The University of Melbourne. When the hospital opened its Pathology Department in 1939, Kreiger and her staff relocated to its Biochemistry Section. Until her retirement in 1966, Krieger carried out research on high blood pressure in pregnancy, Rhesus immunisation and recurrent miscarriage.

Professor John Gorman

John Gorman completed his medical studies at The University of Melbourne in 1953 and completed a residency in Pathology at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Centre. Gorman was appointed Professor of Pathology at Columbia University and Director of the Blood Bank at Presbyterian Hospital (NY). In the 1960s, he and colleagues – Dr Vincent Freda and Dr William Pollock – discovered a method to prevent Rh disease which was introduced as a pharmaceutical product, RhoGAM® in 1968. From 1981 to 2000, Gorman was a Professor of Pathology and Director of the Blood Bank at New York University.

Maternal Health Committee (NHMRC)

The 1995 Maternal Health Committee was established by NHMRC, following a request from the Department of Human Services and Health, to formulate guidelines for the use of Rh D immunoglobulin in Rh-negative women. Membership of the working party included: Dr David Woodhouse (Chairman), Dr Sandra Deveridge, Dr Michael J Fett, Mr John Haines, Professor David Henderson Smart, Ms Dell Horey, Dr Vince Roche, Dr John Smoleniec, Dr Amanda Thomson and Dr Jan White.

Guidelines

NHMRC Guidelines

NHMRC guidelines are intended to promote health, prevent harm, encourage best practice and reduce waste. They are developed by multidisciplinary committees or panels that follow a rigorous evidence-based approach. NHMRC guidelines are based on a review of the available evidence and follow transparent development and decision-making processes. They are informed by the judgement of evidence by experts, and the views of consumers, community groups and other people affected by the guidelines. Regarding ethical issues, NHMRC guidelines reflect the community's range of attitudes and concerns.

Find more information on NHMRC guidelines.

NBA Guidelines

The NBA funds and manages the development of evidence based clinical guidelines on patient blood management and the prophylactic use of Rh D immunoglobulin. NBA guidelines are developed by clinical experts and are based on the results of systematic reviews of the medical literature and expert consensus. The NBA Guideline development is based on the NHMRC standards. Find more information about NBA patient blood management guidelines.

Partner(s)

References

This case study was developed with in partnership with The National Blood Authority and Australian Red Cross Lifeblood.

The following sources were consulted for this case study:

1Hirani R, Weinert N, Irving DO. The distribution of ABO RhD blood groups in Australia, based on blood donor and blood sample pathology data. Medical Journal of Australia. 2022 Apr 4;216(6):291-5.

2NCI Dictionary of Cancer terms: Antigen. National Cancer Institute. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/antigen

3Building Centres of Excellence. Australia, Victoria: Royal Women's Hospital; 2008.

4Pollack W, Gorman JG, Freda VJ, Ascari WQ, Allen AE, Baker WJ. Results of clinical trials of Rhogam in women. Rhesus haemolytic disease. 1968;8(3):151-3.

5Finning, K., Martin, P. and Daniels, G. ‘A Clinical Service in the UK to Predict Fetal Rh (Rhesus) D Blood Group Using Free Fetal DNA in Maternal Plasma’. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004; 1022: 119-23.

6Finning K, Martin P, Soothill PW, Avent ND. ‘Prediction of fetal D status from maternal plasma: introduction of a new non-invasive fetal RHD genotyping service’. Transfusion 2002; 42:1079-85

7Hyland, C.A., Gardener, G.J., Davies, H., Ahvenainen, M., Flower, R.L., Irwin, D., Morris, J.M., Ward, C.M. and Hyett, J.A. ‘Evaluation of non-invasive prenatal RHD genotyping of the fetus’. MJA 2009; 191:1, 21-25.

8Australian Red Cross Lifeblood. Australia's pioneering Rh Program turns 50 [Internet]. Lifeblood. 2017. Available from: https://transfusion.com.au/bsib_july2017_2

9Dean M. Wanted: Rh D negative donors. Australian Prescriber. 2000;23(2):36–8.

10Australian Red Cross Lifeblood. Pregnancy, anti–D and plasma [Internet]. Lifeblood. Available from: https://www.lifeblood.com.au/blood/learn-about-blood/plasma/anti-D

11Thorpe R, Kruse SP, Masser BM. It is about who you know (and how you help them): Insights from staff and donors about how to recruit and retain a panel of committed anti-D donors. Vox Sang. 2022;1–7.