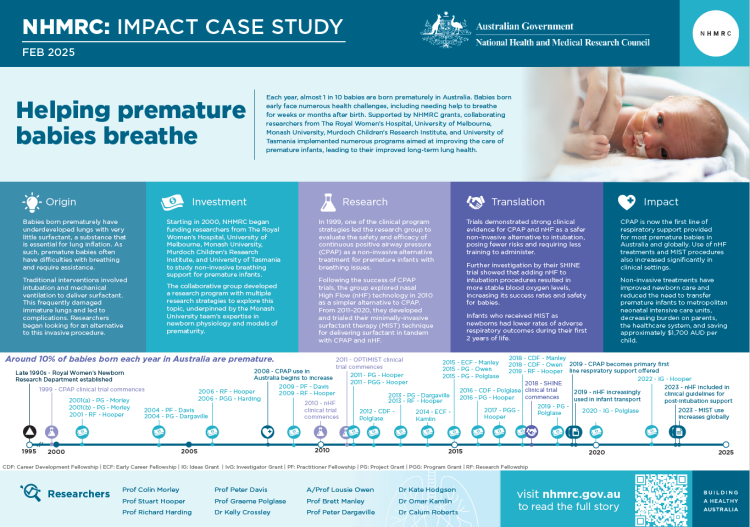

Each year, almost 1 in 10 babies are born prematurely in Australia.1 Babies born early face numerous health challenges, including needing help to breathe for weeks or months after birth. For babies born very preterm, lung complications can continue well into childhood. Supported by NHMRC grants, collaborating researchers from The Royal Women’s Hospital, University of Melbourne, Monash University, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, and University of Tasmania implemented numerous programs aimed at improving the care of premature infants, leading to their improved long-term lung health.

Origin

The gestational age of a baby has significant implications for their health, with poorer outcomes reported for infants who were born prematurely. Gestational age refers to the number of completed weeks in a pregnancy and is reported in three categories: preterm (less than 37 weeks); term (37 to 41 weeks); and post-term (42 weeks and over).1

In 2022, almost 10% of the 297,725 babies born in Australia were preterm. Of these, one out of five (20%) were very preterm births (28 to 32 weeks) or extremely preterm births (less than 28 weeks).1 Extremely preterm babies have the highest complications and the lowest survival rate.

Lung development of babies starts very early in pregnancy, occurring in several stages. The final stage begins around 32 weeks when a substance called surfactant is produced in the lungs. Surfactant prevents air sacs in the lungs from collapsing and is essential for the lungs to inflate and fill with air. Babies born early have very little surfactant and have underdeveloped and immature lungs, which often leads to a condition called Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS).

Traditionally, many preterm infants were thought to be unable to breathe for themselves at birth, and needed surfactant treatment to treat or prevent RDS. The babies consistently underwent intubation (placing a breathing tube directly into the windpipe) to give surfactant and for ‘mechanical ventilation’ (support from a breathing machine). However, these treatments, whilst lifesaving, damage immature lungs. Intubation is a high-risk and technically challenging procedure that frequently leads to complications such as infection, airway injuries, and developmental problems.2 Long-term use of oxygen treatments for RDS also leads to inflammation and scarring of the lungs, causing a chronic lung disease called bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD).3

RDS and BPD are the primary clinical complications facing babies born preterm, and the likelihood of having them increases the earlier the baby is born. Clinicians began searching for a way to provide respiratory treatment to preterm infants with RDS while avoiding issues associated with invasive intubation.

Credit: The Royal Women’s Hospital

Investment

The first NHMRC-funded research into premature infants was secured in 2000 with Colin Morley (Royal Women’s Hospital) and Stuart Hooper (Monash University) receiving a Project Grant to study breathing support at birth in the most premature babies.

Since then, collaborating researchers at The Royal Women’s Hospital, the University of Melbourne, Monash University, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, and the University of Tasmania have received over 50 NHMRC grants to study newborn health and outcomes for premature infants. This collaboration has investigated an extensive range of newborn outcomes through physiological principles, models of prematurity and clinical trials, 4 of which are described in this report.

The collaborative group included Colin Morley, Stuart Hooper, Peter Davis, Richard Harding, Peter Dargaville, Graeme Polglase, Kelly Crossley, Louise Owen, Brett Manley, Omar Kamlin, Calum Roberts, and Kate Hodgson.

The PDF poster version of this case study includes a graphical timeline showing NHMRC grants provided and other events described in the case study.

Research and Translation

The Royal Women’s Hospital Newborn Research Department was established in the late 1990s, led by Colin Morley and Peter Davis. The Women’s Newborn Research department were interested in improving the care of preterm infants in the delivery room and the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Morley began collaborating with Stuart Hooper from the Monash University Physiology Department to investigate a non-invasive technology called continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in very preterm infants. This initial partnership laid the groundwork for an extensive and successful research program.

From 1999 to 2006, the research team conducted the first delivery room study to compare routine intubation and ventilation against CPAP in very preterm infants. Their ‘COIN’ trial recruited over 600 infants born at 25-28 weeks’ gestation in Australia, New Zealand, Europe, and the US. The trial showed that more than half of the CPAP-treated babies managed without intubation for surfactant treatment. At one month, the CPAP-treated babies were also less likely to require oxygen therapy than intubated babies.

This landmark study, published in 2008, was the first randomised controlled trial (RCT) to provide strong evidence that not all babies need to be intubated at birth and that early CPAP treatment was achievable for extremely preterm babies.3 Several subsequent studies found similar results and when combined in a meta-analysis, showed that there was also a reduction in BPD.4 This evidence, alongside other advantages of CPAP including easier operation, less training, and potentially fewer risks, made CPAP an attractive alternative to invasive ventilation.5

Meanwhile, the wider research group continued to secure NHMRC funding and explored avenues to improve non-invasive respiratory support, publishing several studies that underpinned subsequent clinical trials. While CPAP was a strong alternative to intubation, it carried risks for nasal injuries and air leaking outside the lung causing its collapse, called pneumothorax. Given this heightened risk of CPAP-induced pneumothorax, experienced medical and nursing professionals were needed to administer CPAP safely and efficiently. This requirement often precluded its use in smaller special care nurseries in Australia.6

In the mid-2000s, a new, less complicated form of respiratory support called nasal High Flow (nHF) was emerging. This new nHF treatment was being used in newborns without evidence of safety or efficacy, and trials were urgently needed. The research team led three RCTs investigating the use of nHF as a CPAP alternative in preterm infants from 2010 to 2017 that included more than 1,600 babies.6,7,8 Their findings showed that most babies did very well with nHF and suffered fewer complications than they did with CPAP. Offering nHF was now a viable option for smaller hospitals, instead of transferring babies to big centres or requiring specialised staff for CPAP or intubation treatments.

Credit: The Royal Women’s Hospital

Many very preterm and extremely preterm infants could now be managed with CPAP and nHF from birth. However, some babies experienced significant surfactant deficiency which required surfactant treatment to be administered directly into the lungs (using intubation). Alternatives to intubation needed to be found, and the ‘minimally-invasive surfactant therapy’ (MIST) technique was developed to deliver surfactant to babies receiving CPAP or nHF therapy using a thin catheter, which is less invasive than traditional intubation tubes.

From 2011 to 2020, the team, in collaboration with the University of Tasmania, conducted the NHMRC-supported ‘OPTIMIST’ trial of MIST.9 The trial found that MIST-treated babies had half the rate of intubation and pneumothorax, survivors had less BPD, needed less respiratory support, had less need for home oxygen treatment, and were less likely to have a hospital admission with respiratory problems in their first 2 years.10

Most recently, the team applied lessons from the earlier trials to the intubation procedure to improve its safety and success. Their innovative ‘SHINE’ trial (2018-2021) tested the use of nHF during the intubation procedure in more than 250 intubation events. They found that adding nHF made intubation more successful and safer for babies, giving more stable blood oxygen levels.11

Outcomes and impacts

With evidence that CPAP could be used from birth in extremely preterm infants, major international organisations such as the European Guidelines for the Management of RDS and the American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care updated their guidelines in 2010 to incorporate the CPAP technique.12,13

By 2019, 80% of babies 25-28 weeks’ gestation born in Australia and New Zealand were being offered CPAP as first line respiratory support.14 Surveys in Europe and North America reported similar practice changes, with intubation and mechanical ventilation now mostly reserved for preterm newborns in whom CPAP treatment has failed.15,16

The increasing use of CPAP and nHF in non-intensive care settings also led to reductions in the need to transfer preterm infants to metropolitan neonatal intensive care units for care.17 CPAP use in local hospitals keeps more mothers and babies together in their birth hospitals, reduces burdens on health care systems, parents, and the need for hospital transfers, achieving cost savings of approximately $1,700 AUD per child.18

The publication of evidence supporting nHF for post-intubation support in babies was followed by a huge increase in its use; from 22% of infants <28 weeks in Australia/New Zealand in 2009 to almost 75% in 2020.19,20 Nasal HF is preferred by nursing staff and parents as it is more comfortable, easier to apply, easier to use in small and remote hospitals, and a cost-effective alternative to CPAP.21,22,23 Its use has been incorporated into Victorian state-wide transport guidelines for supporting babies moving between hospitals.24 Recommendations for nHF use now also appear in multiple international guidelines and resources, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the National Institute of Clinical Excellence UK.25,26

In an economic analysis, the OPTIMIST team showed that the MIST procedure was cost effective and it has subsequently become increasingly used around the world.27 In 2022, the Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network first reported surfactant delivery by this route, showing that almost 25% of infants less than 32 weeks’ gestation received their first surfactant dose via MIST.28

The team’s evidence for using nHF during neonatal intubation has become a world-first strategy changing newborn care delivery.10 It has already been included in two international guidelines and the treatment implemented in 6 countries (Australia, England, Scotland, USA, Latvia, Canada). The Melbourne team are refining its use and further studies of nHF use at birth are underway.29,30,31

Researchers

Professor Colin Morley

Colin J Morley received a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery at the University of Cambridge. He received a Diploma of Child Health from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow and was awarded a Doctor of Medicine from the University of Cambridge. He has held positions at The Royal Women’s Hospital, The Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne and The University of Melbourne, Australia.

Professor Stuart Hooper

Stuart Hooper completed a PhD at Monash University. He then undertook postdoctoral research at Monash University and the University of Western Ontario in Canada. He has been President of the Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand and currently runs the Fetal and Neonatal Health research group at the Hudson institute of Medical Research.

Professor Richard Harding

Richard Harding completed his PhD in neuroscience before pursuing postdoctoral research examining the neurological control of breathing at the University of Oxford. He is now an Emeritus Professor with the Department of Anatomy and Developmental Biology at Monash University. His research focuses on Respiratory Development and Programming.

Professor Peter Davis

Peter G Davis is currently the Professor of Neonatal Medicine at The Royal Women’s Hospital. He completed his neonatal fellowship training at McMaster University in Canada and completed an MD through the University of Melbourne. He is a substantial contributor to the Cochrane Collaboration and a member of the neonatal subcommittee of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation.

Professor Graeme Polglase

Graeme R Polglase completed his PhD and much of his postdoctoral work at Monash University. He is currently a professor at the Hudson Institute of Medical Research in Melbourne and Deputy Centre Head of The Ritchie Centre. Graeme is a fetal and neonatal physiologist with expertise in respiratory and cardiovascular transition at birth, and leads strategies to improve newborn resuscitation.

Dr Kelly Crossley

Kelly J Crossley completed her PhD at Monash University and has been an integral part of the newborn collaboration for almost 20 years. She is currently a senior research scientist at the Hudson Institute of Medial Research in Melbourne. Kelly is a perinatal physiologist with expertise in developing models of prematurity for perinatal research.

Associate Professor Louise Owen

Louise S Owen completed specialist medical training in the United Kingdom and a PhD at the University of Bristol. She is currently a Neonatal Consultant in the Newborn Intensive Care Unit at the Royal Women’s Hospital and performs research through her positions at the University of Melbourne and the Murdoch Children's Research Institute. She is a Melbourne University Dame Kate Campbell Fellow.

Professor Brett Manley

Brett J Manley completed his PhD with Peter Davis and Louise Owen at The Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne. He is currently a Consultant Neonatologist at The Royal Women's Hospital in Melbourne and a Professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Newborn Health at The University of Melbourne. He is a Melbourne University Dame Kate Campbell Fellow.

Professor Peter Dargaville

Peter A Dargaville trained at the Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne and the University of California specialising in neonatology. He was director of the Neonatal and Paediatric Intensive Care at the Royal Hobart Hospital from 2005 to 2015. He is currently a clinician researcher at the Royal Hobart Hospital and the Menzies Institute for Medical Research at the University of Tasmania. His research focuses on the development and implementation of novel therapies for lung disease in newborns.

Other researchers

Dr Kate A Hodgson completed her PhD with Peter Davis, Brett Manley, Omar Kamlin and Louise Owen at The Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne. She is currently a Consultant Neonatologist at The Royal Women's Hospital in Melbourne.

Dr Omar Kamlin completed his PhD with Peter Davis and Colin Morley at The Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne where he worked as a Consultant Neonatologist.

Dr Calum Roberts completed his PhD with Peter Davis, Brett Manley and Louise Owen at The Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne. He is currently a Consultant Neonatologist at Monash Health and a Senior Research Fellow, in the Department of Paediatrics at Monash University.

Partner

This case study was developed with input from Associate Professor Louise Owen, Professor Peter Davis and Professor Brett Manley, and in partnership with The Royal Women’s Hospital.

References

The information and images from which impact case studies are produced may be obtained from a number of sources including our case study partner, NHMRC’s internal records and publicly available materials. Key sources of information consulted for this case study include:

1 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's mothers and babies [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024 [cited 2024 Oct. 2]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/australias-mothers-babies

2 Spence K, Barr P, Cochrane Neonatal Group. Nasal versus oral intubation for mechanical ventilation of newborn infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1996 Sep 1;2010(1).

3 Morley CJ, Davis PG, Doyle LW, Brion LP, Hascoet JM, Carlin JB. Nasal CPAP or intubation at birth for very preterm infants. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008 Feb 14;358(7):700-8.

4 Schmölzer GM, Kumar M, Pichler G, Aziz K, O’Reilly M, Cheung PY. Non-invasive versus invasive respiratory support in preterm infants at birth: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 2013 Oct 17;347.

5 DiBlasi RM. Nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for the respiratory care of the newborn infant. Respiratory care. 2009 Sep 1;54(9):1209-35.

6 Manley BJ, Arnolda GR, Wright IM, Owen LS, Foster JP, Huang L, Roberts CT, Clark TL, Fan WQ, Fang AY, Marshall IR. Nasal high-flow therapy for newborn infants in special care nurseries. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019 May 23;380(21):2031-40.

7 Manley BJ, Owen LS, Doyle LW, Andersen CC, Cartwright DW, Pritchard MA, Donath SM, Davis PG. High-flow nasal cannulae in very preterm infants after extubation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013 Oct 10;369(15):1425-33.

8 Roberts CT, Owen LS, Manley BJ, Frøisland DH, Donath SM, Dalziel KM, Pritchard MA, Cartwright DW, Collins CL, Malhotra A, Davis PG. Nasal high-flow therapy for primary respiratory support in preterm infants. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016 Sep 22;375(12):1142-51.

9 Dargaville PA, Kamlin CO, Orsini F, Wang X, De Paoli AG, Kutman HG, Cetinkaya M, Kornhauser-Cerar L, Derrick M, Özkan H, Hulzebos CV. Effect of minimally invasive surfactant therapy vs sham treatment on death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome: the OPTIMIST-A randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2021 Dec 28;326(24):2478-87.

10 Dargaville PA, Kamlin CO, Orsini F, Wang X, De Paoli AG, Kutman HG, Cetinkaya M, Kornhauser-Cerar L, Derrick M, Özkan H, Hulzebos CV. Two-year outcomes after minimally invasive surfactant therapy in preterm infants: follow-up of the OPTIMIST-A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023 Sep 19;330(11):1054-63.

11 Hodgson KA, Owen LS, Kamlin CO, Roberts CT, Newman SE, Francis KL, Donath SM, Davis PG, Manley BJ. Nasal high-flow therapy during neonatal endotracheal intubation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022 Apr 28;386(17):1627-37.

12 Sweet DG, Carnielli V, Greisen G, Hallman M, Ozek E, Plavka R, Saugstad OD, Simeoni U, Speer CP, Halliday HL. European consensus guidelines on the management of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome in preterm infants–2010 update. Neonatology. 2010 Jun 10;97(4):402-17.

13 Kattwinkel J, Perlman JM, Aziz K, Colby C, Fairchild K, Gallagher J, Hazinski MF, Halamek LP, Kumar P, Little G, McGowan JE. Part 15: neonatal resuscitation: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010 Nov 2;122(18_suppl_3):S909-19.

14 Hodgson KA, Owen LS, Lui K, Shah V. Neonatal Golden Hour: A survey of Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network units' early stabilisation practices for very preterm infants. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2021 Jul;57(7):990-7.

15 Moretti C, Gizzi C, Gagliardi L, Petrillo F, Ventura ML, Trevisanuto D, Lista G, Dellacà RL, Beke A, Buonocore G, Charitou A, Cucerea M, Filipović-Grčić B, Jeckova NG, Koç E, Saldanha J, Sanchez-Luna M, Stoniene D, Varendi H, Vertecchi G, Mosca F. A Survey of the Union of European Neonatal and Perinatal Societies on Neonatal Respiratory Care in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Children. 2024 Jan 26;11(2):158.

16 Shah V, Hodgson K, Seshia M, Dunn M, Schmölzer GM. Golden hour management practices for infants< 32 weeks gestational age in Canada. Paediatrics & Child Health. 2018 Jun 12;23(4):e70-6.

17 Safer Care Victoria. Nasal continuous positive airway pressure (NCPAP) for neonates [Internet]. Victoria (AU): Safer Care Victoria; 2013 [updated 2016 October; cited 2024 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.safercare.vic.gov.au/best-practice-improvement/clinical-guidance/neonatal/nasal-continuous-positive-airway-pressure-ncpap-for-neonates

18 Buckmaster AG, Arnolda G, Wright IM, Foster JP, Henderson-Smart DJ. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Therapy for infants with respiratory distress in non–tertiary care centers: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2007 Sep 1;120(3):509-18.

19 Roberts CT, Owen LS, Manley BJ, Davis PG. High-flow support in very preterm infants in Australia and New Zealand. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2016 Sep 1;101(5):F401-3.

20 Chow SSW, Creighton P, Chambers GM, Lui K. Report of the Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network 2020 [Internet]. Sydney (AU): Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network; 2022 [cited 2024 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.anznn.net/Portals/0/AnnualReports/Report%20of%20the%20Australian%20and%20New%20Zealand%20Neonatal%20Network%202020_amended.pdf

21 Manley BJ, Owen LS, Doyle LW, Andersen CC, Cartwright DW, Pritchard MA, Donath SM, Roberts CT, Manley BJ, Dawson JA, Davis PG. Nursing perceptions of high‐flow nasal cannulae treatment for very preterm infants. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2014 Oct;50(10):806-10.

22 Klingenberg C, Pettersen M, Hansen EA, Gustavsen LJ, Dahl IA, Leknessund A, Kaaresen PI, Nordhov M. Patient comfort during treatment with heated humidified high flow nasal cannulae versus nasal continuous positive airway pressure: a randomised cross-over trial. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2014 Mar 1;99(2):F134-7.

23 Huang L, Roberts CT, Manley BJ, Owen LS, Davis PG, Dalziel KM. Cost-effectiveness analysis of nasal continuous positive airway pressure versus nasal high flow therapy as primary support for infants born preterm. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2018 May 1;196:58-64.

24 Abraham V, Manley BJ, Owen LS, Stewart MJ, Davis PG, Roberts CT. Nasal high-flow during neonatal and infant transport in Victoria, Australia. Acta Paediatr. 2019 Apr 1;108(4):768-9.

25 Cummings JJ, Polin RA, Watterberg KL, Poindexter B, Benitz WE, Eichenwald EC, Poindexter BB, Stewart DL, Aucott SW, Goldsmith JP, Puopolo KM. Noninvasive respiratory support. Pediatrics. 2016 Jan 1;137(1).

26 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Specialist neonatal respiratory care for babies born preterm (NG124) [Internet]. UK: NICE; 2019 [cited 2024 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng124/resources/specialist-neonatal-respiratory-care-for-babies-born-preterm-pdf-66141658884805

27 Cox I, de Graaff B, Otahal P, Kamlin O, Orsini F, De Paoli A, Clark H, Soll R, Carlin J, Davis P, Dargaville P. EE56 Minimally Invasive Surfactant Treatment Versus Standard Therapy in Preterm Infants at Birth (OPTIMIST-A TRIAL): An Analysis of Initial Hospitalisation Costs and Resource Consumption. Value in Health. 2023 Jun 1;26(6):S69.

28 Chow SSW, Creighton P, Holberton JR, Chambers GM, Lui K. Report of the Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network 2022 [Internet]. Sydney (AU): Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network; 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.anznn.net/Portals/0/AnnualReports/Report%20of%20the%20Australian%20and%20New%20Zealand%20Neonatal%20Network%202022.pdf

29 Huang Y, Zhao J, Hua X, Luo K, Shi Y, Lin Z, Tang J, Feng Z, Mu D, Evidence‐Based Medicine Group, Neonatologist Society, Chinese Medical Doctor Association. Guidelines for high‐flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in neonates (2022). Journal of Evidence‐Based Medicine. 2023 Sep;16(3):394-413.

30 Disma N, Asai T, Cools E, Cronin A, Engelhardt T, Fiadjoe J, Fuchs A, Garcia-Marcinkiewicz A, Habre W, Heath C, Johansen M. Airway management in neonates and infants: European society of Anaesthesiology and intensive care and British: Journal of anaesthesia: joint guidelines. European Journal of Anaesthesiology| EJA. 2024 Jan 1;41(1):3-23.

31 Hodgson KA, Selvakumaran S, Francis KL, Owen LS, Newman SE, Kamlin CO, Donath S, Roberts CT, Davis PG, Manley BJ. Predictors of successful neonatal intubation in inexperienced operators: a secondary, non-randomised analysis of the SHINE trial. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2024 Jul 5.