Table of contents

CEO Communique – February 2022

Key points

- NHMRC is committed to ensuring that all researchers have equal opportunity to undertake health and medical research regardless of their gender. We will work towards this goal until it is achieved.

- Progress has been made towards gender equity in grant numbers and value across the NHMRC grant program overall and near-equal proportions of female and male applicants have been funded for the past 5 years.

- Three rounds of the Investigator Grant scheme have now been completed. In each round, men have applied in higher numbers and a higher proportion of grant applications from men have been funded. As a result, more grants have been awarded to men than women and men have received more funding than women.

- The main factor underlying this disparity is the continuing predominance of male applicants at the most senior levels of the scheme, where budgets tend to be largest.

- Structural priority funding has boosted the number of Investigator Grants awarded to women. Gender disparities would be worse without such priority funding.

- NHMRC is actively considering further initiatives it can take to advance gender equity in its grant schemes.

The purpose of this communique is to present a detailed analysis of funding outcomes by gender for NHMRC’s Investigator Grant scheme. While some of the data presented here are already available on NHMRC’s website, additional data and information about the scheme are provided to support discussion of the funding outcomes and potential approaches to reducing gender disparities in this scheme.

(Two webinars were held to discuss the barriers to gender equity in the health and medical research sector and the levers available to NHMRC to work towards equity. Recordings of the webinars held on 24 February 2022 and 3 March 2022 are available on NHMRC's Vimeo.)

1. Snapshot of funding outcomes by gender in NHMRC’s grant program 2012–2021

NHMRC has been concerned for many years about the lower representation of women among applicants and grant holders and other gender disparities in funding outcomes. As summarised at Gender Equity, we have introduced a range of initiatives over the last 10 years to foster gender equity in NHMRC’s grant program.

The following figures summarise data for lead Chief Investigators (CIAs) by gender and the year of application across the whole grant program since 2012. The complete datasets from 2013 are available at Outcomes of funding.

%20%E2%80%93%20all%20schemes.JPG)

X/NS denotes CIAs who did not state their gender or declared it as Indeterminate/Intersex/Unspecified.

Note that the total number of grants has declined from 2019 in part because of the introduction of NHMRC’s new grant program in which funding for fellowship salaries and research support was consolidated in the Investigator Grant scheme and application numbers to certain schemes were capped.

%20%E2%80%93%20all%20schemes.JPG)

Figure 3. Funded rates by gender of CIA (2012–2021) – all schemes

%20%E2%80%93%20all%20schemes.JPG)

‘Funded rate’ is the number of grants awarded as a percentage of the number of applications. ‘All applicants’ include CIAs who did not state their gender or declared it as Indeterminate/Intersex/Unspecified. Arrow indicates the year of introduction of structural priority funding.

The data in Figures 1 to 3 show a progressive improvement in the representation of women among lead investigators and in the gender balance of grants and funds awarded over the last 10 years. In 2021, women submitted 45.6% of applications and were awarded 46.3% of grants and 44.4% of funds (compared with 41.0%, 38.4% and 31.6%, respectively in 2012).

It is likely that at least 3 factors have influenced these outcomes:

- NHMRC initiatives to promote gender equity in funding outcomes

- the introduction of NHMRC’s new grant program in 2019

- changes in female representation in the health and medical research sector more broadly.

Funded rates for women and men have been close to equal since 2017. This can be attributed, at least in part, to the introduction of structural priority funding, a direct intervention to fund ‘near-miss’ applications in structural priority areas, of which gender equality (support for female CIAs) is one. First applied in 2017 and 2018 in the former Project Grant scheme, it has now been used in all three rounds of the Investigator and Ideas Grant schemes where unadjusted funded rates are consistently lower for female than for male CIAs.

Gender outcomes differ by scheme. For example, it is common for success rates to be markedly higher for female than male CIAs in the Centres of Research Excellence Scheme. Also, in the first two rounds of the Synergy Grant scheme, more grants have been awarded to teams led by women (60% of grants in 2019 and 53% in 2021) than men. This is a significant change from the Synergy Grant scheme’s nearest analogue before 2019, the Program Grant scheme – in the final year of that scheme, all eight Program Grants awarded were led by men. This change likely reflects the inclusion of diversity in the selection criteria for the Synergy Grant scheme.

Progress has been made towards gender equity in application numbers, grants awarded and funds awarded across the NHMRC grant program overall.

Overall funded rates for female and male lead investigators have been close to equal for the past 5 years.

2. Investigator Grants 2019–2021

More men than women applied for and were awarded Investigator Grants, and higher overall funding was awarded to men than to women, in each of the first three years of this scheme (See Investigator Grants 2021 Outcomes Factsheet).

The Investigator Grant scheme is NHMRC’s largest scheme. Gender disparities in application numbers and outcomes therefore attract, and warrant, particular attention.

2.1 Intent and design of the scheme

The Investigator Grant scheme was introduced in 2018–19 as one of four new schemes in NHMRC’s reformed grant program. The purpose of the scheme is to provide a salary (if needed) and a flexible research support package (RSP) for outstanding researchers at all career stages.

Until 2018, under NHMRC’s previous grant program, eligible researchers could apply for a fellowship for their salary and for one or more other research grants to support the costs of their research. There were five distinct fellowship schemes of varying duration and each with its own rules: Early Career Fellowships, Translating Research into Practice (TRIP) Fellowships, Career Development Fellowships, Practitioner Fellowships and Research Fellowships (the last of these with four levels: Senior Research Fellowship A and B, Principal Research Fellowship and Senior Principal Research Fellowship). The main schemes from which fellows (and researchers who received their salary from another funder or their institution) obtained research support were the Project and Program Grant schemes. Any researcher could apply for and hold up to six Project Grants or a single Program Grant at one time. However, the separation of the fellow’s salary from their research support led to the anomaly that they could win one without the other.

'It was as though my collaborator and I made a whole person between us. At any one time, one of us had a fellowship and the other had research funding.'

In the new grant program, all the previous fellowship schemes have been replaced by the Investigator Grant scheme with five levels of seniority: Emerging Leadership levels 1 and 2 (EL1, EL2) and Leadership levels 1, 2 and 3 (L1, L2, L3). Each award includes an RSP to replace the funding that fellows could previously seek through Project or Program Grants, consolidating salary and research support into a single 5-year grant. The size of the RSP is determined in two ways:

- For Emerging Leadership Fellows, the RSP depends on their level ($50,000 per annum for EL1 and $200,000 per annum for EL2)

- For Leadership Fellows, the RSP depends on their position in the ranked list of assessor scores ($300,000, $400,000, $500,000 or $600,000 per annum) regardless of their level; the intention is that the largest RSPs are not automatically awarded to the most senior applicants.

NHMRC’s grant program is funded from the Medical Research Endowment Account (MREA). The total budget for the Investigator Grant scheme is currently $365 million per annum, about 40% of the MREA, and comprises a $335 million baseline budget and a $30 million structural priority budget. The total budget was based on the proportion of NHMRC funding previously awarded to all fellows and equivalent researchers through the various Fellowship schemes and the Project and Program Grant schemes. For this reason, Investigator Grant holders are not eligible to apply for Ideas Grants. The allocation is split further into separate budgets for EL1, EL2 and Leadership grants. These allocations and the distribution of Leadership RSPs between four tiers were also based on the distribution of funding in the former grant program.

Investigator Grants are attractive because of the autonomy and financial security they give awardees to do their best research. They have therefore been highly competitive in each round to date.

2.2 Selection criteria

Investigator Grant applications are assessed by peer reviewers against the following selection criteria:

- Track record relative to opportunity (70%) – the value of the individual’s past achievements, comprising: publications (35%), research impact on knowledge, health, the economy and/or society (20%), and leadership (15%)

- Knowledge gain (30%) – the quality of the proposed research and the significance of the knowledge gained.

The process for developing Investigator Grant funding recommendations after peer review is outlined in Appendix A.

2.3 Key changes to the scheme for the 2021 round

Two important changes were made for the 2021 Investigator Grant round.

First, to help peer reviewers assess applicants’ track records relative to opportunity, all applicants were required to describe their career context, including individual circumstances and opportunities for research. The intention was to embed the consideration of individual circumstances in the assessment of all track records. Stakeholder feedback and data from both applicant and peer reviewer surveys indicated that the information collected was useful in the description and assessment of career circumstances.

Second, the Statements of Expectations were revised to provide applicants and peer reviewers with more guidance on the expectations of applicants at each level of the scheme. Feedback from the previous Investigator Grant rounds suggested that many applicants had applied at a lower level than expected based on their research experience. For the 2021 round, applicants were required to provide a justification for their selected category and level of Investigator Grant and advised that the justification would be considered by peer reviewers in assessing the applicant’s track record relative to opportunity. The intention was to ensure a fair ‘like-for-like’ competition between applicants at each level.

Figure 4 shows a change in distribution of application numbers in 2021, with less skewing of Emerging Leadership applications to EL1 and Leadership applications to L1 than in 2019 and 2020. The data suggest that the additional guidance in the 2021 Statements of Expectations has influenced level selection by applicants.

2.4 Gender analysis of the first three rounds of the scheme

This section analyses Investigator Grant outcomes by gender over the first three years of the scheme. Unless otherwise indicated, all data shown below include grants supported with structural priority funding (of which two were awarded to men and 37 were awarded to women over three years – see below for more detail).

2.4.1 Applications, grants and budgets awarded by gender

.JPG)

Figure 5 (left hand side) shows the marked decline in the proportion of applications submitted by women with seniority, the familiar ‘scissor graph’. Although absolute numbers of applications generally decline for both women and men with seniority (see below – Figure 6), the rate of decline for women is more precipitous than for men. This repeats a pattern seen in NHMRC’s former Fellowship schemes before 2019 and broadly reflects the distribution of women and men by academic seniority in Australia’s health and medical research sector Gender and the Research Workforce | Section 3 | 11 Medical and Health Sciences).

Approximately 4 times more men than women have applied at L3 in each year of the Investigator Grant scheme. A similar picture is seen at institutional level. For the six institutions that received the highest number of Investigator Grants in every year of the scheme (Universities of Melbourne, Sydney and Queensland, Monash University, UNSW and WEHI), there were on average 4.3 times more male than female L3 applicants over the three years. For three of those institutions, this ratio was 7 or more.

The shape of the scissor graph varies from year to year. It will be important to see whether the narrowing of the gap at L1 and L2 observed in 2021 continues.

Figure 5 (right hand side) shows that funded rates are routinely highest at L3 and lowest at EL2/L1. This ‘squeeze in the middle’ was also seen in the former Fellowship schemes. The relative funded rates for women and men vary by level and by year; as there is no clear pattern, it is difficult to draw conclusions from differences at any one level in a single year. The overall difference in funded rates by gender has varied from year to year but has consistently favoured men (by 3.6% in 2019, 1.3% in 2020 and 3.6% in 2021) (data not shown).

This gap would have been higher at all levels of the scheme without structural priority funding. As shown in Table 1 below, the overall difference in funded rates between men and women for the three years was 2.8% with structural priority funding and 5.2% without it. The structural priority budget was allocated to support four priorities in 2019 –2021: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health researchers and research, female lead investigators and health services research. More women than men were supported through structural priority funding because support for female investigators was one of the priorities and because more women than men were awarded grants through the other priorities.

| Level | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. grants without SP funding* (funded rate) | No. grants with SP funding (funded rate) | No. grants without SP funding (funded rate) | No. grants with SP funding (funded rate) | |

| EL1 | 120 (15.0%) | 123 (15.4%) | 113 (11.0%) | 137 (13.4%) |

| EL2 | 66 (10.8%) | 69 (11.3%) | 48 (6.8%) | 66 (9.3%) |

| L1 | 58 (8.0%) | 59 (8.1%) | 32 (6.0%) | 47 (8.8%) |

| L2 | 58 (15.1%) | 59 (15.4%) | 29 (14.2%) | 37 (18.1%) |

| L3 | 112 (41.8%) | 112 (41.8%) | 21 (30.9%) | 26 (38.2%) |

| All | 414 (14.8%) | 422 (15.1%) | 243 (9.6%) | 313 (12.3%) |

| *SP, structural priority | ||||

The following Figures 6 and 7 present the numbers of applications and grants, and the total funds awarded, by level and gender. “All applicants” include those who did not state their gender or declared it as Indeterminate/Intersex/Unspecified.

.JPG)

Figure 7. Total Investigator Grant funding awarded by level and gender (2019–2021)

.JPG)

Figures 6 and 7 together show that the higher number of grants awarded to men and, in particular, the higher overall funding awarded to men largely reflect their higher representation at the most senior levels of the Investigator Grant scheme, especially L3.

The number of women applying for Investigator Grants declined precipitously with seniority compared with men.

The predominance of male applicants at the most senior levels of the scheme, where budgets tend to be largest, is a major factor underlying the award of more grants and more overall funding to men than women.

Structural priority funding reduced the gap in funded rates between men and women at all levels of the scheme.

2.4.2 Analysis of Leadership grant sizes by gender

The following analyses focus on grant sizes at the Leadership levels where the greatest gender differences are observed.

| Year | Leadership level | Average grant size | Significance test (t-test) p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| 2019 | L1 | $2,371,545 | $2,005,549 | 0.046* |

| L2 | $2,083,300 | $2,106,765 | 0.865 | |

| L3 | $2,215,695 | $2,252,255 | 0.756 | |

| 2020 | L1 | $2,296,886 | $2,135,200 | 0.331 |

| L2 | $2,109,376 | $2,157,206 | 0.826 | |

| L3 | $2,408,054 | $2,482,261 | 0.707 | |

| 2021 | L1 | $2,337,577 | $2,081,200 | 0.079 |

| L2 | $2,357,576 | $2,489,546 | 0.495 | |

| L3 | $2,639,787 | $2,647,109 | 0.979 | |

| *The difference between the average grant sizes awarded to men and women is significant at the 5% level. | ||||

Table 2 shows that, with one exception (L1 in 2019), the average grant size awarded to men and women was not significantly different at the 5% level. However, Investigator Grant sizes are affected by several factors as outlined below and these may differ between men and women.

Salary

- Applicants have the option not to request a salary from their grant or they may be ineligible to receive a salary (for example, if they hold a senior administrative position).

- Eligible applicants have the option to request a part-time salary from their grant for personal or professional reasons.

Research Support Package

- Applicants also have the option to seek less than a full RSP (for example, if they are employed part-time).

- The size of the RSP depends on the final grant score following peer review, not seniority.

- Grants awarded with structural priority funding receive the lowest RSP.

- The awarded RSP is reduced if the applicant has continuing Ideas, Project or Program Grant funding until the earlier grants have ceased.

The following tables show the salary requests, RSP sizes and RSP reductions for awarded Leadership grants by gender. Data are pooled for the three years of the scheme because some group sizes are small and risk identifying individual grant holders.

| Level | Salary requested | Salary not requested | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-time | Part-time (personal) | Part-time (professional) | ||||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| L1 | 49 (83.1%)* | 37 (78.7%) | 0 | 0 | 8 (13.6%) | 8 (17.0%) | 2 (3.4%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| L2 | 37 (62.7%) | 20 (54.1%) | 0 | 0 | 10 (16.9%) | 9 (24.3%) | 12 (20.3%) | 8 (21.6%) |

| L3 | 80 (71.4%) | 21 (80.8%) | 0 | 1 (3.8%) | 7 (6.3%) | 2 (7.7%) | 25 (22.3%) | 2 (7.7%) |

| L1-L3 | 166 (72.2%) | 78 (70.9%) | 0 | 1 (0.9%) | 25 (10.9%) | 19 (17.3%) | 39 (17.0%) | 12 (10.9%) |

| *Percentage of grants awarded by gender in parentheses | ||||||||

Table 3 shows that most grant holders requested a salary from their grant. A higher proportion of women than men requested a part-time salary (almost always for professional reasons). At L3, a higher proportion of men than women did not request a salary. Given the small group sizes, these apparent gender differences may not be significant.

With one exception over the three years of the scheme, all funded applicants requested 100% RSP (data not shown).

| Level | No. grants | Average salary | Average RSP | Average grant size* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| L1 | 59 | 47 | $629,271 (26.9%) | $617,828 (29.7%) | $1,706,027 (73.1%) | $1,464,505 (70.3%) | $2,335,298 (100%) | $2,082,333 (100%) |

| L2 | 59 | 37 | $608,793 (28.1%) | $578,246 (25.7%) | $1,555,958 (71.9%) | $1,669,024 (74.3%) | $2,164,751 (100%) | $2,247,269 (100%) |

| L3 | 112 | 26 | $672,853 (27.8%) | $754,339 (29.9%) | $1,750,278 (72.2%) | $1,766,114 (70.1%) | $2,423,131 (100%) | $2,520,453 (100%) |

| *Grant size is the sum of the salary and the RSP. Figures in parentheses are the proportion of the average grant size contributed by each component (salary or RSP). | ||||||||

Table 4 suggests modest differences in both directions between men and women in the contribution of RSPs to the average grant size. By two-sample t-tests, these differences were not significant at the 5% level at L1, L2 or L3.

| Year | RSP tier | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. grants | % grants | No. grants | % grants | ||

| 2019 | LT1 | 34 | 40.5% | 22 | 66.7% |

| LT2 | 25 | 29.8% | 7 | 21.2% | |

| LT3 | 14 | 16.7% | 3 | 9.1% | |

| LT4 | 11 | 13.1% | 1 | 3.0% | |

| Total | 84 | 100% | 33 | 100% | |

| 2020 | LT1 | 32 | 43.8% | >25 | 59.5% |

| LT2 | 24 | 32.9% | 6 | 14.3% | |

| LT3 | 10 | 13.7% | 7 | 16.7% | |

| LT4 | 7 | 9.6% | 4 | 9.5% | |

| Total | 73 | 100% | 42 | 100% | |

| 2021 | LT1 | 31 | 42.5% | 22 | 62.9% |

| LT2 | 24 | 32.9% | 5 | 14.3% | |

| LT3 | 10 | 13.7% | 5 | 14.3% | |

| LT4 | 8 | 11.0% | 3 | 8.6% | |

| Total | 73 | 100% | 35 | 100% | |

| *The four RSP tiers are $300,000 (LT1), $400,000 (LT2), $500,000 (LT3) and $600,000 (LT4) per annum. | |||||

Table 5 shows the distribution of RSPs for male and female Leadership fellows. RSPs were awarded from the baseline budget in pre-determined proportions. The distribution of RSPs for female fellows is skewed towards the lower tiers for two reasons: first, a smaller proportion of grants to women from the baseline budget were awarded the highest RSPs (LT3 and LT4) and, second, grants awarded from the structural priority budget received the lowest RSP (LT1), regardless of Leadership level. As noted above, more women than men were supported through structural priority funding (because support for female investigators was one of the structural priorities and because more women than men were awarded grants through the other structural priorities). While structural priority funding enabled additional women to be supported as shown above in Table 1, it contributed to women being awarded a lower average RSP than men (before reductions – see below).

The size of the RSP depends on the final grant score, not seniority. Figure 8 below shows that all four RSP tiers were awarded to Leadership fellows at all three levels of seniority, although the higher tiers were more likely to be awarded to L3 than to L1 or L2.

.JPG)

| Level | RSP tier | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. grants | % grants by level | No. grants | % grants by level | ||

| L1 | LT1 | 25 (24)* | 42.4% | 36 (21) | 76.6% |

| LT2 | 19 (19) | 32.2% | 7 (7) | 14.9% | |

| LT3 | 8 (8) | 13.6% | 2 (2) | 4.3% | |

| LT4 | 7 (7) | 11.9% | 2 (2) | 4.3% | |

| Total | 59 (58) | 100% | 47 (32) | 100% | |

| L2 | LT1 | 32 (31) | 54.2% | 21 (13) | 56.8% |

| LT2 | 20 (20) | 33.9% | 8 (8) | 21.6% | |

| LT3 | 7 (7) | 11.9% | 7 (7) | 18.9% | |

| LT4 | 0 (0) | 0% | 1 (1) | 2.7% | |

| Total | 59 (58) | 100% | 37 (29) | 100% | |

| L3 | LT1 | 40 (40) | 35.7% | 12 (7) | 46.2% |

| LT2 | 34 (34) | 30.4% | 3 (3) | 11.5% | |

| LT3 | 19 (19) | 17.0% | 6 (6) | 23.1% | |

| LT4 | 19 (19) | 17.0% | 5 (5) | 19.2% | |

| Total | 112 (112) | 100% | 26 (21) | 100% | |

| L1-L3 | LT1 | 97 (95) | 42.2% | 69# (41) | 62.7% |

| LT2 | 73 (73) | 31.7% | 18# (18) | 16.4% | |

| LT3 | 34 (34) | 14.8% | 15& (15) | 13.6% | |

| LT4 | 26 (26) | 11.3% | 8& (8) | 7.3% | |

| Total | 230 (228) | 100% | 110 (82) | 100% | |

| *Figures in parentheses are the numbers of grants awarded from the baseline budget. #p<0.05 (grants by tier as a proportion of total for men versus women; two-tailed z-test) &p>0.05 (grants by tier as a proportion of total for men versus women; two-tailed z-test) | |||||

Consistent with Figure 8, Table 6 shows that applicants at all levels were awarded the full range of RSP tiers. For example, 7 men and 2 women at the most junior level (L1) were awarded the largest RSP (LT4); conversely, 40 men and 12 women at L3 were awarded the smallest RSP (LT1). Overall, however, the largest number and the highest proportion of LT4 RSPs were awarded to the most senior applicants. At L3, many more men than women were awarded grants, as already noted, but similar proportions of men and women were awarded the highest RSPs (LT3 and LT4). The skewing towards the award of lower RSPs to women (Table 5) was most marked at L1.

As noted above, the awarded RSP is reduced if the applicant has continuing Ideas, Project or Program Grant funding, until the earlier grants have ceased. Table 7 below looks at whether there were differences between men and women in the proportion of grants with RSP reductions and/or the size of those reductions; such differences would reflect gender differences in previously awarded funding.

| Leadership level | No. grants | No. grants with RSP reduction (average % RSP reduction) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| L1 | 59 | 47 | 46 (17.0%) | 36 (16.8%) |

| L2 | 59 | 37 | 40 (18.8%) | 23 (15.2%) |

| L3 | 112 | 26 | 65 (25.6%) | 16 (22.0%) |

| L1-L3 | 230 | 110 | 151 (21.1%) | 75* (17.4%) |

| *p>0.05 (151/230 versus 75/110; two-tailed z-test) | ||||

Table 7 shows that both the proportion of grants with RSP reductions and the extent of those reductions were similar for men and women.

In general, the average grant sizes awarded to men and women at each Leadership level were not significantly different. The component salaries and RSPs (that together make up the grants) were also not significantly different between men and women.

RSPs awarded to women were skewed towards the lower tiers compared with those awarded to men at L1 but not at the more senior L3.

RSP reductions due to previously awarded funding affected male and female Leadership fellows to a similar extent.

2.4.3 Assessor scores by gender

| Year | Leadership level | Mean final scores | Significance test (t-test) p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| 2019 | L1 | 4.944 | 4.843 | 0.086 |

| L2 | 5.323 | 5.116 | 0.038* | |

| L3 | 5.663 | 5.461 | 0.199 | |

| 2020 | L1 | 5.083 | 5.091 | 0.888 |

| L2 | 5.314 | 5.347 | 0.710 | |

| L3 | 5.709 | 5.638 | 0.615 | |

| 2021 | L1 | 5.142 | 5.015 | 0.026* |

| L2 | 5.261 | 5.191 | 0.271 | |

| L3 | 5.535 | 5.667 | 0.196 | |

| An application’s final score is the average of all assessors’ scores for that application. *The difference between the mean final scores of male and female applications is significant at the 5% level. | ||||

Table 8 shows that mean final scores followed the hierarchy L3>L2>L1 in each year of the scheme; this differential has narrowed for men with each year of the scheme. Although the mean final scores of applications from men were commonly 0.1-0.2 higher than for those from women at each level, these differences usually did not reach significance at the 5% level.

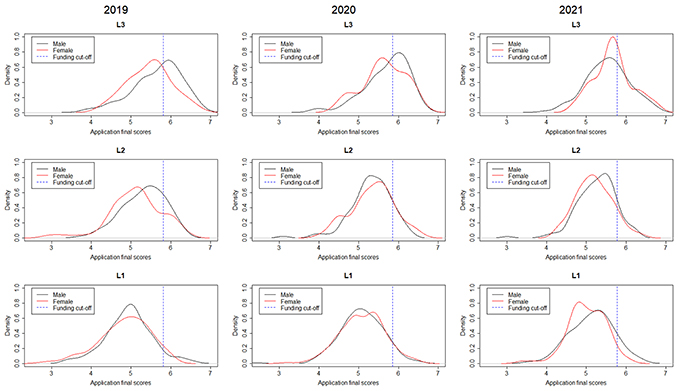

Figure 9 below shows that the distribution of final scores for applications from men and women were sometimes markedly different and affected the proportion of applications above the funding threshold – for example, for L3 in 2019 and L1 in 2021.

*Vertical dotted lines in blue show the lowest score of funded applications (excluding those supported with structural priority funding).

Although mean final scores and the distribution of scores were generally similar for men and women at each level, there were differences in some groups that affected funding outcomes by gender.

2.4.4 Peer reviewers by gender

NHMRC introduced an ‘application-centric’ process to match peer reviewers to applications for the 2021 round of the Investigator Grant scheme. The process used was as follows:

- Potential peer reviewers were identified by NHMRC from among last year’s reviewers, those who self-nominated to participate and those who had previously been awarded an Investigator Grant.

- Reviewers were pre-matched to applications based on research classifications and level (matching Emerging Leadership applications to reviewers at the EL career stage and Leadership applications to reviewers at the Leadership career stage).

- Matched reviewers provided declarations of suitability and conflicts of interest for subsets of applications.

- Each application was assigned to five reviewers based on their suitability/conflict of interest declarations. Reviewers were assigned 10–30 applications each, with an average of 17 for Emerging Leadership reviewers and 20 for Leadership reviewers.

- Reviewers undertook their assessments independently and provided scores and brief written comments.

- Reviewers had access to published peer review guidelines, training materials and a peer review mentor to discuss any issues of policy.

Matching of applications to reviewers relies heavily on data provided by researchers through their Sapphire profiles. As the quality of the data improves and the methodology is refined, it is expected that matching will also improve and fewer declarations will be needed from peer reviewers.

| Competition | Invited1 | Accepted2 | Final3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Not stated | Male | Female | Not stated | Male | Female | Not stated | |

| Total | 425 (51.2%) | 400 (48.2%) | 5 (0.6%) | 287 (51.3%) | 270 (48.3%) | 2 (0.4%) | 243 (51.7%) | 226 (48.1%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Emerging Leadership | 270 | 229 | 4 | 158 | 190 | 2 | 134 | 156 | 1 |

| Leadership | 155 | 171 | 1 | 129 | 80 | 0 | 109 | 70 | 0 |

| 1 Number who were invited to review Investigator Grant applications at any stage in the round 2 Number who accepted an invitation to review Investigator Grant applications before suitability and conflict of interest declarations 3 Number who assessed applications | |||||||||

Table 9 shows that, overall, more men than women were invited to undertake peer review for the 2021 Investigator Grant round; a similar ratio of men to women accepted these invitations and completed reviews. For Emerging Leadership applications, although more men than women were invited to review, more women accepted invitations and undertook reviews. For Leadership applications, more women than men were invited to review but the acceptance rate was notably lower.

While NHMRC is working towards achieving gender parity among peer reviewers at all levels, this is constrained by availability and the need to avoid overburdening any group, such as senior women.

Slightly more men than women were invited to assess Investigator Grant applications, accepted those invitations and completed assessments. More women than men assessed Emerging Leadership applications and more men than women assessed Leadership applications.

3. Conclusions from the analyses of funding outcomes

Across the whole NHMRC grant program since 2012, significant progress has been made towards parity between men and women in application numbers and both the number and value of grants awarded (Figures 1–3). Funded rates have been close to equal for men and women since the introduction of structural priority funding in 2017.

Over the first three years of the Investigator Grant scheme:

- More men than women applied for grants, a higher proportion of male applicants were awarded grants and greater overall funding was awarded to men than to women.

- The number and proportion of female applicants declined precipitously with seniority compared with men each year, consistent with the lower representation of women at senior levels of the academic sector (Figure 5).

- Overall, the funded rate was lower for female applicants than male applicants each year, although there was no consistent pattern in the relative funded rates of men and women across the five levels of the scheme from year to year (Figure 5).

- Structural priority funding reduced the gap in funded rates between men and women at all levels of the scheme (Table 1).

- The average grant sizes awarded to men and women at each Leadership level were generally similar (Tables 2 and 4).

- RSPs awarded to women were skewed towards the lower-value tiers compared with those awarded to men at L1 – but not at the more senior L3 (Tables 5 and 6).

- RSP reductions due to previously awarded funding affected male and female Leadership fellows to a similar extent (Table 7).

- Mean final scores of applications from men and women at each level were generally similar (Table 8). However, there were differences in the distributions of scores that contributed to higher funded rates and budgets for men than women in some instances (Figure 9).

- A slight majority of men participated as peer reviewers for the scheme overall, with a majority of women for Emerging Leadership applications and a marked majority of men for Leadership applications, again reflecting their representation in the sector (Table 9).

The data suggest that the single biggest factor contributing to the greater total value of Investigator Grants awarded to men than women is the higher proportion of male applicants at the most senior levels of the scheme.

4. Possible initiatives to overcome gender disparities in Investigator Grant funding

While progress towards gender equity has been made across NHMRC’s grant program overall, the persistent gender disparities in Investigator Grant outcomes are concerning. Funding outcomes are the result of independent peer review of submitted applications. The submitted applications and the conduct of peer review are affected by many influences that are outside NHMRC’s visibility and control. NHMRC can, however, influence outcomes through the funding structure of a scheme and the design of selection criteria and peer review processes.

Researchers and others have suggested a range of possible interventions that would involve changes to the Investigator Grant funding structure or peer review. Some of these suggestions are outlined below with a brief discussion of steps that have already been taken and the issues that would need to be considered before deciding whether or how to implement them.

NHMRC does not have a settled position on the best way to address this problem and is open to considering a range of possible changes, some of which would be more feasible than others.

While not discussed here, we would also need to consider how to address disadvantage for non-binary applicants, as well as how to manage applications where the CI’s gender is not stated.

4.1 Possible changes to the funding structure

1. Introduce quotas for women

In principle, NHMRC could set a minimum proportion of Investigator Grants to be awarded to women. If NHMRC were to do this, there are several questions to consider:

- Should the quota be determined by the proportion of female applicants or a higher number?

- Should the quota be the same in each of the three competitions (EL1, EL2 and L), noting that female representation has been different in each of them and has varied from year to year?

- Should the quota determine grant numbers or the overall funding awarded? Because Investigator Grant budgets are affected by several parameters (application level, final score [for Leadership grants], salary request, grants already held), outcomes would differ depending on the type of quota.

- If, as could be predicted, quotas significantly reduce Investigator Grant funding to senior male applicants, would this lead to increased gender disparities in other schemes, such as Ideas Grants, by shifting those applicants to those schemes?

2. Create separate Investigator Grant budgets for men and women and manage them as separate competitions

The three Investigator Grant budgets (EL1, EL2 and L) are currently set before each round.

- Should each of the three budgets be split equally between men and women?

- This might lead to women receiving fewer grants or less funding than now in one or more of the competitions in some years (most likely at EL1 or EL2).

- It might also lead to women having a much higher funded rate than men at the most senior levels of the scheme because of women’s markedly lower representation among applicants at these levels.

- If this approach is adopted for Investigator Grants, should it be extended to other schemes, even when more women than men are currently funded?

3. Equalise funded rates for men and women

NHMRC’s structural priority initiative has already achieved equal funded rates for women and men in the Ideas Grant scheme by funding additional near-miss grants led by women. Ideas Grant budgets are determined by the applicants, sometimes modified on the advice of peer reviewers, and are not affected by the funding source (baseline budget or structural priority budget). This approach can therefore achieve equal funded rates in the Ideas Grant scheme without unintended consequences.

Structural priority funding has reduced the gap in funded rates for women and men in the Investigator Grant scheme and average grant budgets have been similar despite the fact that women supported through structural priority funding receive the lowest RSP.

- Should the structural priority budget be increased or made flexible to guarantee equal funded rates for men and women?

- Should funded rates be equalised in each of the three competitions or at every level, or only where women’s funded rates are lower than those of men?

4. Encourage advancement of women’s careers by increasing funding for L1 and L2 within the Leadership category

Separate competitions at each level within the Leadership category (as in the Emerging Leadership category) would enable NHMRC to set budgets for each level in advance and apply gender equity initiatives selectively.

- Should the budgets for L1, L2 and L3 grants be predetermined and, if so, how should they be set?

- Should gender equity initiatives (such as structural priority funding or quotas) be applied selectively or across all levels?

- Should the four tiers of RSP be distributed within each level, for instance, so that the same proportion of L1, L2 and L3 awardees receive the highest RSP?

5. Require institutions to submit equal numbers of applications from women and men

Changing the representation of women in the applicant pool would be likely to affect outcomes provided the distribution of application quality is similar between women and men.

- Should institutions be required to submit equal numbers by gender in each of the competitions (or at every level)? Would this mean that some men would not be allowed to apply from institutions with few female researchers?

- Should this approach only be required of large NHMRC Administering Institutions with sufficient researchers of both genders?

4.2 Possible changes to peer review

1. Review assessment criteria and weightings for gender bias

The issue of gendered language was considered in the development of the assessment criteria and category descriptors. For example, the Leadership element of the track record assessment framework aims to recognise different types of leadership, including less hierarchical activities such as mentoring, building and maintaining collaborative networks, team building and community engagement.

- Do any elements of the assessment criteria favour gendered achievements (recognising that peer reviewers are required to take individual circumstances into account when assessing track records relative to opportunity)?

- To what extent do the current weightings of the assessment criteria favour one gender?

2. Fund the research, not the person

This approach was considered in the re-design of NHMRC’s grant program. It was recognised that past success can be an indicator of future success and that it was important to invest in people with outstanding research achievement and promise – this is the purpose of the Investigator Grant scheme and the reason it includes track record assessment as a major selection criterion.

It was also recognised that the best and most innovative ideas can come from researchers who do not have outstanding track records – the Ideas Grant scheme is intended to support such researchers and for this reason does not include track record assessment.

3. Blind peer reviewers to applicant’s name

In principle, blinded review could be implemented in the Investigator Grant scheme for the Knowledge Gain selection criterion with peer review undertaken as a two-stage process to allow unblinded review of the applicant’s track record. As peer reviewers are expected to consider key publications and detailed descriptions of past research impact and research leadership, it would be difficult to implement blinded peer review of track records.

NHMRC is considering the feasibility of introducing two-stage peer review of Ideas Grant applications with blinded review against the Research Quality, Innovation and Creativity and Significance selection criteria. If implemented, this would be an important test of whether blinded review altered the relative distribution of scores for male and female CIAs for criteria other than track record.

NHMRC is also hoping to learn more from the Women in STEM Ambassador’s trial of anonymised review of grant applications.

4. Ensure there are equal numbers of male and female peer reviewers

Equal numbers of female and male peer reviewers are assumed to foster equity in outcomes.

NHMRC seeks to achieve equal numbers of female and male peer reviewers across the grant program, including the large-scale Investigator and Ideas Grant schemes. Equal numbers continue to be difficult to achieve among senior researchers without overburdening a small number of senior women. Opportunities for people with family responsibilities (generally women) to participate in peer review of these large schemes have been increased by the removal of Grant Review Panel (GRP) meetings.

5. Bring back Grant Review Panels

While NHMRC understands the reasons some researchers are calling for the return of GRPs, we note that marked gender disparities were prominent features of both the Fellowship and Project Grant schemes over the many years leading up to the introduction of the current grant program, despite their reliance on GRPs to reach a final score for each application. It was also difficult for many people with family responsibilities to participate in GRP meetings, despite initiatives to support their involvement.

NHMRC is continuing to improve the matching of independent reviewers to each application and to develop guidance materials and training modules to support high-quality peer review, calibration between assessors and application of the Relative to Opportunity Policy. A report currently being finalised on analyses undertaken by NHMRC’s Peer Review Analysis Committee will provide more information on scoring by independent reviewers.

5. Concluding comments and next steps

The data presented here suggest that the single biggest factor contributing to the greater total number and value of Investigator Grants awarded to men than women is the higher proportion of male applicants at the most senior levels of the scheme.

This is not a surprising finding. It has long been the case that most senior positions in the health and medical research sector, as in many other professions, have been held by men. While the gap is narrowing, progress is very slow. NHMRC is well aware of the many different factors at play – including gender differences in societal expectations and roles, professional opportunities and obligations, experiences of harassment and bias, whether conscious or unconscious. NHMRC’s Relative to Opportunity Policy asks peer reviewers to consider relevant circumstances when assessing an applicant’s track record but this is focussed on the individual’s specific circumstances rather than underlying gender differences in career opportunities.

While the finding is not surprising, the issue is challenging to address because the predominance of men amongst funded applicants reflects their representation at senior levels of the sector overall and because it is so marked at the L3 level. This issue is compounded by high funded rates at L3 which in turn reflect the many rounds of ‘selection’ through which the most senior researchers (male and female) have passed to meet the expectations of an L3 applicant. Without additional funding, any substantial intervention to address the predominance of men at L3 would have significant ramifications – from pushing those highly competitive applicants into other NHMRC grant schemes to the potential loss of senior leaders and mentors from the sector.

The challenge for NHMRC is to find a path that provides the greatest possible opportunity for women, early and mid-career researchers and others who are currently missing out on funding, at great cost to the research sector, without risking a significant loss of experience and expertise at the more senior levels where progress towards gender equity in the sector is slow.

The issues discussed in this communique will be high priorities among the topics on which NHMRC will seek advice from its Research Committee and Women in Health Science Committee over the coming year. With the appointment of Research Committee announced on 16 December 2021 and the appointment of the next Women in Health Science Committee (to be chaired by a member of Research Committee) for 2021–2024 in progress, meetings of both committees will commence in early 2022.

As the data and discussion presented here illustrate, addressing gender disparities in the Investigator Grant scheme is not straightforward. Any significant change to the structure of the scheme must be based on careful analysis and modelling of potential effects across the sector to avoid unintended consequences.

There also may not be a single answer. In addition to considering structural changes to the scheme, NHMRC will continue to look for ways to provide clear guidance to the research sector and to ensure the highest standards of peer review.

We rely on engagement with the research sector, through our advisory committees and peak bodies and informally, to understand the impact of NHMRC’s funding policies on Australian health and medical research and to solve the issues that emerge. We will continue to welcome feedback and ideas as these discussions progress.

We also rely on people of all genders applying for Investigator Grants at all levels. We recognise that low funded rates are discouraging for many but we hope that you will take heart from the progress that has been made towards gender equity in NHMRC’s grant program and the outstanding results achieved by women who won Investigator Grants at the highest levels in 2021.

NHMRC is committed to achieving a gender-equal research sector – where all researchers have equal opportunity to pursue their research ambitions and which draws on the whole pool of talent needed to meet present and future health challenges. We will work on the issues discussed in this communique until they are resolved. We look to the research sector itself, including administering institutions, senior research leaders and peer reviewers, to work with us to support the advancement of women’s research careers and to eliminate all forms of bias. We will reach our goal with your support.

Appendix A – Process for developing Investigator Grant funding recommendations

In 2021, the following steps were followed to arrive at funding recommendations for submission to the Minister for Health.

- Each application was independently assessed against the selection criteria (Section 2.2) by up to 5 peer reviewers, chosen for their suitability and lack of conflicts of interest for that application.

- There were three separate competitions, each with their own budget pre-determined on the advice of Research Committee in approximately the ratio 2:1:3 for EL1, EL2 and Leadership (for example, L1, L2 and L3 applicants competed within a single budget allocation).

- The final score for each application was the arithmetic mean of the scores of the assessors.

- Final scores were ranked in a list for each competition.

- For the EL1 and EL2 competitions, the available budget was allocated starting at the top of the ranked list until it ran out.

- For the Leadership competition, the four tiers of Research Support Package (RSP) were allocated from highest (LT4) to lowest (LT1) in a pre-determined ratio from the top of the ranked list down to the funding cut-off to obtain the final grant budget for each funded application. The available budget was allocated starting at the top of the ranked list until it ran out.

- Once the baseline budget ($335 million) had been allocated for each competition as described above, an additional $15 million to support Early and Mid-Career Researchers was applied to the EL1 and EL2 competitions (for 2021 only, as part of NHMRC’s response to the impacts of COVID-19 on the research sector).

- The structural priority budget ($30 million) was then allocated to high-scoring, ‘near-miss’ applications below the funding cut-off in one or more of the structural priority areas in the following order:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander chief investigators

- Female chief investigators

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research

- Health services research.

- The structural priority budget was allocated to EL1, EL2 and Leadership applications in the same approximate ratio as the baseline budget. Leadership grants awarded through structural priority funding received the lowest tier of RSP (LT1; $300,000 per annum).

- An allocation of $9 million for dementia-related research available for the 2021 funding round was used to support additional eligible EL1 and EL2 applications.

Having pre-determined rules for developing the funding recommendations protects the integrity of the process. The budget allocation to Investigator Grants and other schemes is determined on the advice of Research Committee and endorsed by NHMRC Council early in the calendar year, before application numbers and characteristics for each scheme are known. The allocation of the Investigator Grant budget between the EL1, EL2 and Leadership competitions is also determined on the advice of Research Committee before application numbers and characteristics are known.

.JPG)